It is often tempting for outside observers to judge a society or community solely by its traditions, rituals and festivals, to bestow a significance and seriousness onto events beyond that which they hold for their participants, to see superstition and fear in theatre and frivolity. Equally, of course, the reverse can be true for those involved, leading to a refusal to recognise the serious intent that underpins their festivities.

The event which takes place at the crow tree is one of the community’s least talked about rituals, and consequently can be assumed to be among its most serious. Indeed, there appears to be no written record of the ritual at all, although there are verified accounts of the tree used in the ritual itself dating back to the 15th Century. While the community’s own folklore suggests the ceremony has always taken place, nothing certain about its origins are recorded, and no speculations about its meaning would be offered to me.

The ritual takes place on February the 29th, during the second leap year after the birth of a father’s eldest daughter. The distinction of it being the father’s eldest daughter is an important one, as it means no man can participate in the ritual more than once, whereas a woman might well be required to participate both as a daughter and later as a mother.

(The strict criteria can lead to several convoluted possibilities where the mothers of daughters are concerned. For example, a mother’s first daughter might not be the father’s first daughter, and in this case the ritual would not be required. However, this same mother’s second daughter might then be fathered by a different man, one who has not fathered a daughter before, and so it would be this child that would necessitate the ritual. And of course this hypothetical mother could have more daughters by more new fathers, and so on. Indeed, it is possible for a mother to have to participate in the ritual with each of her daughters, while another woman may never have to, regardless of the number of daughters she has.)

Due to the fixed date of the event combined with the unfixed timing of a child’s birth, the daughter can be anywhere between the age of 4 and exactly 8 when she participates in the ritual. A child born on February the 29th would be the eldest possible participant, and a child born on February the 28th during a leap year would be the youngest.

If the child, the father or the mother have died before the ritual has taken place then a lament is sung by the surviving members of the family at the edge of the field where the ceremonial tree, or crow tree, resides. In these circumstances it is not permitted for the survivors to approach the tree itself during the course of the day.

In recent years, due to the decline in births within the community, it has been rare for there to be more than one family needing to perform the ritual in any given leap year, and indeed in some recent leap years the event has not taken place at all.

In times of a more populous community, however, when multiple rituals were to be carried out during the same day, the participating families were ordered by the age of the child involved, with the eldest girl first and youngest last – a reflection, perhaps, of the length of time they had been waiting to perform. On busy days it was said that, despite there being no apparent communication between the families, each group would arrive in the correct order, equally spaced apart, and that all the rituals would be finished in good time, well before the sun had set.

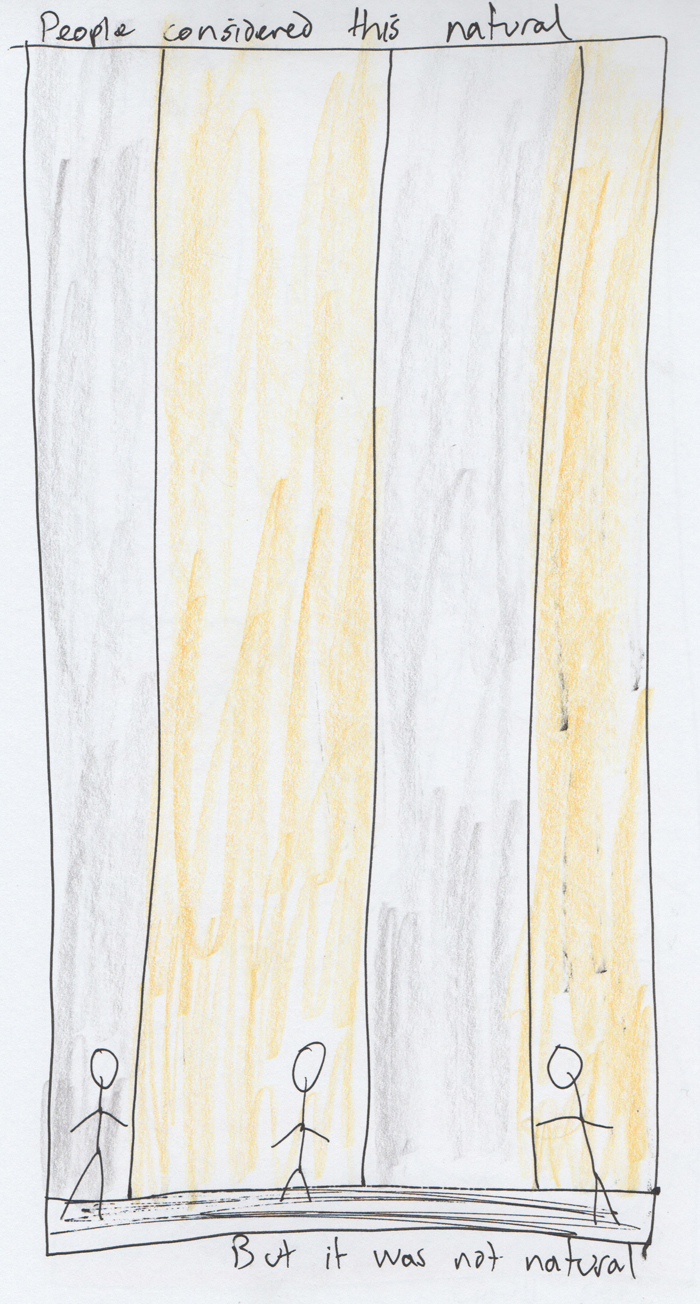

The ritual itself is one of the most sombre in the community’s complex calendar. No work is conducted on the day itself, and it is traditional for everyone who is not directly involved to stay inside their own houses, although this is not compulsory. No costumes are worn, and the tools used are not ceremonial objects, instead being everyday household objects or workplace items.

The ceremony starts with the father leaving his house at dawn. He makes his way to the edge of the field and waits by the gate. The mother and daughter do not hurry, although usually they will arrive before noon, and always before dusk. The mother carries with her a pail filled with breadcrumbs, offal, fish guts, bones, butter. The daughter carries a length of rope and a knife. When they arrive at the gate to the field, the father wordlessly leads the way in and they walk together to the crow tree at the centre of the field.

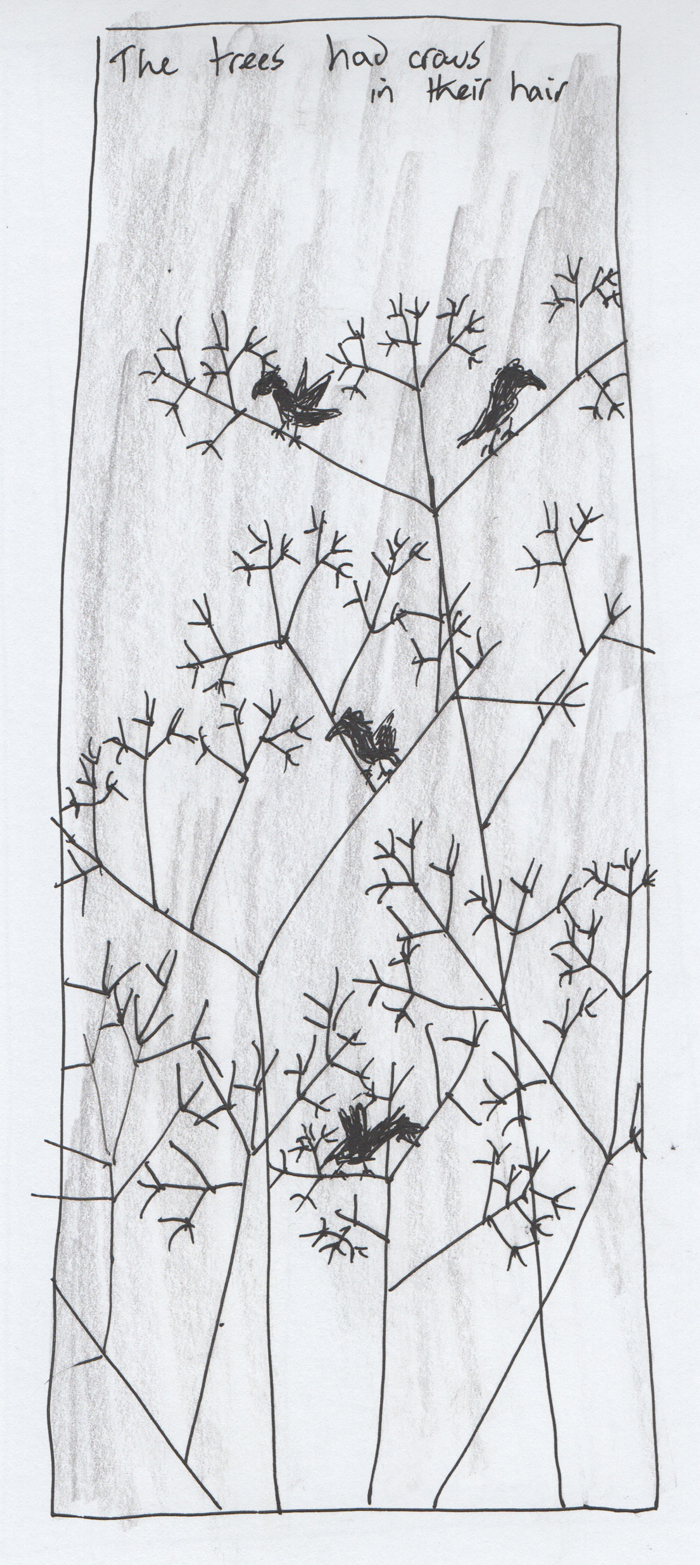

The crow tree is a long dead oak, its trunk and branches bleached white as bone by the sun. Other dead oak trees dot the field, but the crow tree is the only one that remains completely bare of ivy or lichen. It is believed that the trees in the field were killed by the sea hundreds of years ago, although the field is many miles inland. The trees themselves are so cold and solid it is tempting to believe they are actually made of stone.

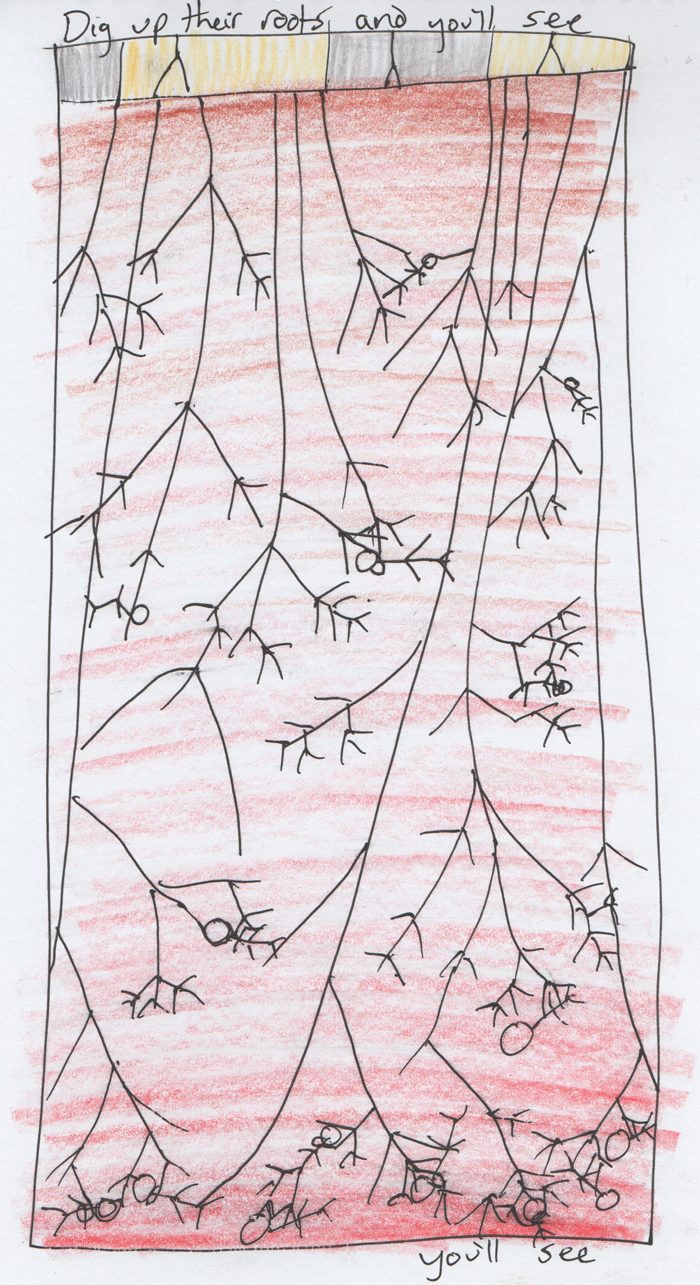

The father stands with his back to the tree. The rope is tied around his left wrist, looped round the tree, and then secured around his right wrist. The daughter pushes her knife into her father’s belly as deeply as she can.

“Speak,” she says, and her father speaks.

They listen. His words go unrecorded.

“Sleep,” says the mother, and, removing the knife from his belly, she slits his throat.

His body is cut down from the tree and dragged a short way from the trunk. The food from the bucket is spread in a circle around him. The knife is placed in the pail, and the women, hand in hand, leave.

Overnight the crows come down from the tree and feed, either upon the flesh of beasts or the flesh of man. In the morning, as the crows return to their roosts, the father is reborn.

Thus judged, some fathers make their way back to town, bucket and knife in hand, and return to their former lives. Others leave, and are not known to be missed.

__________

Notes:

1. Written in April, 2010

2. This appeared in the “Rituals” issue of Here Comes Everyone magazine, in January 2019

__________

If you like the things you've read here please consider subscribing to my patreon or my ko-fi. Patreon subscribers get not just early access to content and also the occasional gift, but also my eternal gratitude. Which I'm not sure is very useful, but is certainly very real.(Ko-fi contributors probably only get the gratitude I'm afraid, but please get in touch if you want more). Thank you!