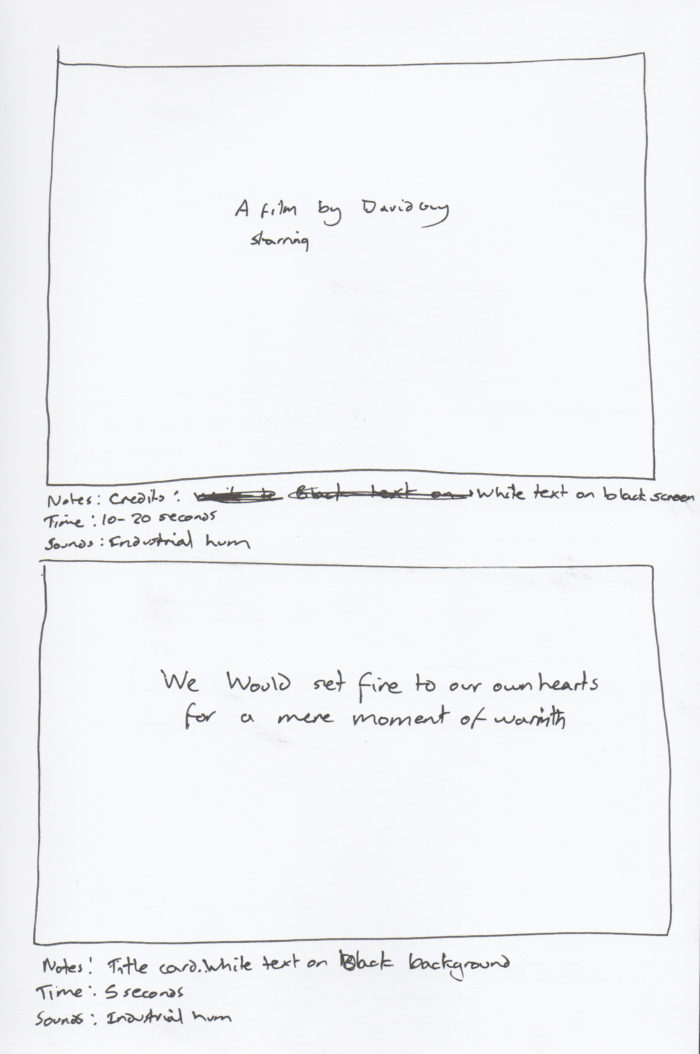

Chapter 1

how did I get here how did I get here how did I get here how did I get here how did I get here how did I get here how did I get here how didi i get ehere how did i egt here how did ieget howdherit ehre

***

suffocating, screaming, pleading make it stop make it stop make it stop but it never stops

the pressure and the pain

building

until it feels

like I’m going to burst

as i die i wake

***

Sometimes I wonder if the only paths that exist are the ones that I have walked down. If it is the mind that makes them real.

***

I am where I am supposed to be, at the address they gave me. There’s nothing here apart from a row of condemned houses, the windows boarded up, the drainpipes and the streetlamps all coated in an undrying paint to deter you from climbing

breaking

entering

***

I find a dead bird in my garden. A sparrow, or a starling, maybe.

I’m not sure of the difference.

Its head is turned to one side, a single droplet of blood ready to burst in its slightly open beak, and its chest has been ripped open. Whatever was once inside has gone.

***

I spend the afternoon writing the report. I tell them what I saw.

I have no idea if it is what they want to hear.

I am never given any indication, of anything. Whatever I tell them, the pay is always the same. Sometimes I have to wait longer for the money to come, and with it the next address.

I cannot tell if this is a judgement on what I say.

***

A dog is barking at me, straining on its leash, lips curled back in a snarl that reveals all of its teeth. Its owner holds him back, feet planted wide, both hands holding grimly onto the leash.

A fisherman at sea in the middle of a storm.

I watch the dog, its powerful jaws, its hate and desire, wishing that the lead would slip through the man’s fingers and the beast would be free to leap at me, its jaws biting my wrist, grinding their way through to the bone as I try to hold it off. The ligaments sever in my arm, my hand goes limp. The dog knocks me to the floor and goes for the throat.

I never scream or cry. Calm acceptance, no fighting, no attempts at escape. Everything soundless, slow, beautiful.

I see myself from above. The blood spreads around me as if I’m giving birth.

***

I post the report and come straight home. I lock the door, close the curtains, sleep before the sun even begins to set.

***

In my dreams it is a city. The streets are more tightly packed, the buildings sometimes older. The river is gone, replaced by a plain that stretches off beyond the High Street.

There is a castle, and passages beneath it, narrow cobbled paths spiralling in on themselves.

There are streets I do not know.

There are hills and there are holes.

The core stays the same, the familiar still there within the expanded whole. At the frayed edges of my memory I know it all, every street and every turn, but only after, when I awake. While I’m there I’m either lost or oblivious.

And always alone.

***

A new letter, containing:

a new address (in the town in which I live)

five ten pound notes

a return address (in a town I do not know)

Everything is always different. Everything is always the same.

***

I walk along streets I’ve walked a million times before, alleyways and pathways, fields, abandoned gardens, car parks. I count the cats I pass, the broken windows, the bent and dented streetlights, the crushed concrete bollards held together only by their twisted metal spines. I wonder what it would be like to hold a sickle to my throat, the curve of its blade a perfect fit against my neck. I pull it quickly across, a single rotation that cuts a thin smooth line all the way around. Blood flares out. I fall to my knees.

***

The address leads me to what is little more than an empty garage, its doorway rolled halfway up when I arrive.

There is nobody here.

An old mattress is leaning up against the back wall, oil stained and damp with a faint covering of mould. An extension lead marks out a trail across the floor, ending violently in the centre of the room, the plug severed, bare wires splayed out like veins. They point towards a solid lump of refined bitumen, a dark crystal, complex and angular, waiting to melt.

It looks soft, liquid, and I can scarcely believe it is not. I place my hand on it to test its solidity, half expecting my fingers to slip into it, like bones dropped in tar.

I dream of their eventual fossilisation, excavation, discovery, museum display.

***

I am lost in streets I do not know. Leaves pile up in drifts along the pavements, concealing the kerbs as they spread out towards the middle of the road. There are no cars to disturb their slow progress. No people to kick them apart.

Above me a moon as bright as the sun.

***

My bedroom is cold. My sheets feel damp, as do my clothes as I put them on. Later, as I walk to the postbox, the low sun strobes through the railings into my eyes.

I imagine it triggering an epileptic fit. I drop to the ground, my body convulsing freely in the loneliness of the street. No one comes to help. My letter slips away in the breeze, a final ponderous butterfly before the end of the year.

***

The post arrives with a new address. I do not know what day it is.

***

Snow outside. Deep, silent. The everyday boundaries of the town obliterated by its spread. Garden indistinguishable from pavement, pavement from road, road from field.

Without these lines

I feel lost

every step

a

possible

transgression

from the public

into the private.

***

The address is a road I do not recognise. Its position on my various maps is inconsistent, sometimes absent. The sun sets and I have still not found it.

***

I look at my footprints in the snow. The journey lines I trace out on my maps every evening are here made physical, echoes of my movement, my speed and my weight. The further back they go the harder it is to discern which are mine and which are not. My past lost in a confusion of information.

***

I slip and fall and land heavily on my back. The snow surrounds me, holds me in a thick embrace.

I can see the moon, a delicate sliver of crystal beyond the frozen sky.

My breath rises up towards it.

I can feel the warmth seeping out of me, down into the snow, into the earth.

I make no attempt to move.

***

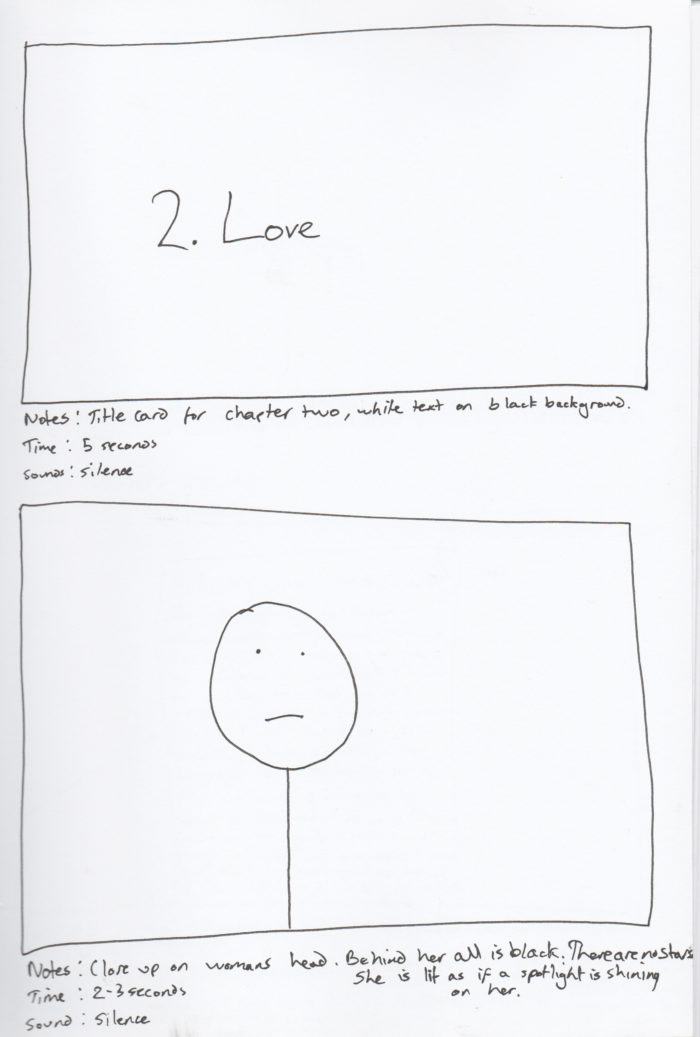

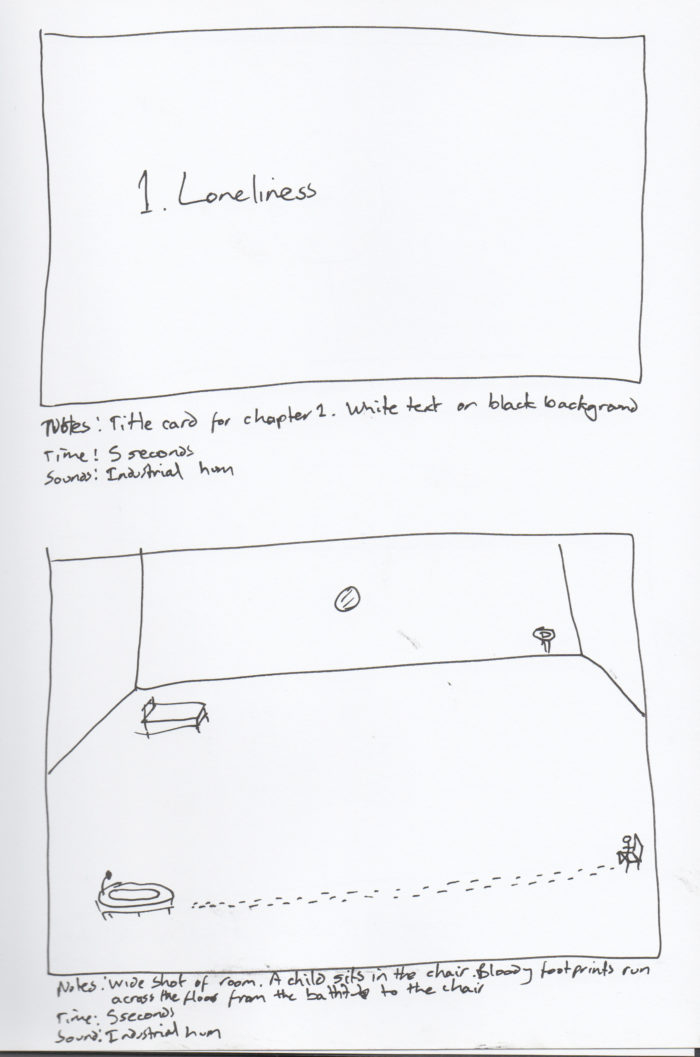

Chapter 2

A map is not just a representation of space but of time as well. The date is as important as the names. Without both you will never find your way.

***

He kept searching. He kept walking. At night he would study his maps, again and again. Occasionally he would absentmindedly give his globe a spin and watch the world rotate before him. He imagined himself a traveller on the static surface of the moon, looking always at the ever moving earth above.

***

He can watch the town grow by looking at his maps in chronological order. Between the earliest ones there are the greatest gaps in date, sometimes over a century or more, and there are vast disparities in the methods of representation. But despite this he feels he can see the town as it was, barely changing from century to century, a few houses here, a church or two, roads and farms that probably date back even further, pre-Roman, pre-pre-Roman. A thousand years of gradual change in a handful of images.

The maps get more accurate as time passes, but more homogenous. They become more frequent, and yet with this decrease in the periods between them the rate of change accelerates, as if each map must contain a certain amount of new data, the publication of the new map forcing the changes, rather than the other way round.

New roads appear, new buildings, canals.

The railway comes.

The river becomes a constant, instead of a snake twisting slowly across the landscape, across time. Eventually the sea is reclaimed, first as marshland, then eventually as farmland. The town expands, contracts briefly between the wars, expands on and on.

Through it all some things stay the same. The roads into and out of the town (one north, crossing the river where it narrows invitingly; one east, which follows the river towards the sea; one west, towards the city; two south, not towards but from the villages there) seem fixed. The churches, once they appear, do not move.

The school itself has not moved for 400 years, but it does grow, keeping pace with the town, while simultaneously the fields around it shrink, a constant creep of houses encroaching across the borders.

The railway goes.

***

He has other maps. A series of detailed layouts of the High Street, each shop marked with its occupant, in ten year increments from just after the war to a few years ago, the final map showing a sudden increase in units marked “vacant”. He has plans of the park, from its construction in the 19th century through various renovations and re-landscapings over the century or more since.

There are charts of farm boundaries, boat moorings. Power cables, phone lines. The drainage network, where over the years you can see the old brooks and streams get pulled into it, eventually being buried beneath new houses and new roads, the town slowly forgetting they were ever there.

Public footpaths,

ancient roadways,

bridleways,

cattle lanes.

Tiny badly-labelled maps from flyers showing the directions to Indian takeaways, kebab shops, out of town furniture warehouses, local museums, boot sales, school fetes, birthday parties. Routes of fun runs, cycle races, summer carnivals, remembrance parades, fundraising santa sleigh-rides.

He kept photos — his own and those of others — organised by location and then date, so you could see the slowly changing faces of the town, its buildings and its people. He took photos too of old paintings of old places. There were printouts of each new iteration of the aerial photographs on google maps, and even the entire town at street level (in black and white, to save on ink).

***

Each day he traced out where he had walked during the day on a sheet of acetate. He marked his route in a blue marker, homes and shops entered were marked with red numbers, and the full details listed at the empty edges of the sheet.

He kept these sheets clipped together, grouped a week at a time, the build-up of routes slowly obliterating from view the map fixed beneath as the days and the overlays stacked up.

He aimed each week to walk every road of the town. He could, if he wished, see where he had gone on any given day from the last seven years. If he had laid them all down together the sheets would reach the ceiling.

An ice core representing almost a fifth of his life, and encompassing the entirety of the town.

***

Even with all this he could not find the place he had been tasked to find. Maddeningly, the name cropped up from time to time, map to map, but nowhere consistently. Sometimes it was the provisional name of a road on a new estate that by the next map had been renamed. Later a shop, from before he was born, the proprietor’s name on an old advertisement. The name of an old house long since demolished.

He could find places which contained part of the name, places which were phonetically similar. He walked to every one, and what he wanted was not there.

***

His favourite map was one depicting the Friars’ Path, the old route between the friary in the centre of the town and the abbey just north of the river. The map showed the abbey and the friary separated by the sweep of the river. It showed no other buildings, although a small line marked the bridge across the river. It was not aligned along the north/south axis, but instead had the abbey at the bottom of the page and the friary at the top. The winding path of the river was shown as a straight (but tapering) line, its widest point at the top left hand corner, narrowing down to a tiny sliver as it crossed the page towards the bottom right corner of the map.

The route was marked out in green. It started at the friary, crossed the river at the bridge, and then made its way to the abbey at the bottom of the sheet. But the path was not straight. Between the friary and the bridge, and then again between the bridge and the abbey, the path swerved left and right seemingly without reason, back and forth across the emptiness of the page, as if a length of cotton had been thrown onto the map and left to lay where it fell.

The map revealed a path through a labyrinth without depicting the labyrinth itself. Of the old roads that the friars walked and the obstructions they avoided, there was no trace.

The map as echo.

***

He printed out a new copy of the town map, this time making the width of the page match the circumference of his globe. He took the globe out of its stand and wrapped the map around the equator, so that the east road out of town met the west road. He cut the top and the bottom half of the map into ribbons and folded them down towards the poles. As the strips of the map overlapped each other they formed new networks of roads,

new paths,

a new town.

The river formed a sea that stretched across a third of the northern hemisphere and covered the pole. Fields and gardens were lost in the south, creating an endless tangle of housing estates that formed a tight maze of streets as dense as a thornbush. The two roads that led out of the town to the south formed a loop that surrounded and contained the new maze.

The remains of the ancient wall near the site of the old friary, which previously marked out a large U shape, now formed an equilateral triangle that entirely sectioned off the old ruins, protecting or perhaps imprisoning them within its boundary.

***

He taped the edges of the map down and looked at this tiny new world. His house still existed, but now he had new neighbours. His garden was gone, and the field behind it.

There, at the centre, where the two edges met and the east road bled back into the west. The two truncated names merged to form the address he had been looking for.

***

It was late, and the town was empty. The sky was clear above, the stars bright in the freezing winter air. Frost crunched under his boots, and he walked slowly so as not to slip. He went to the west road because it was marginally nearer.

***

He looked at his globe. This was the point. It looked no different from usual, the road stretching away in a straight line towards both horizons. The frosted tarmac a white scar in the dark.

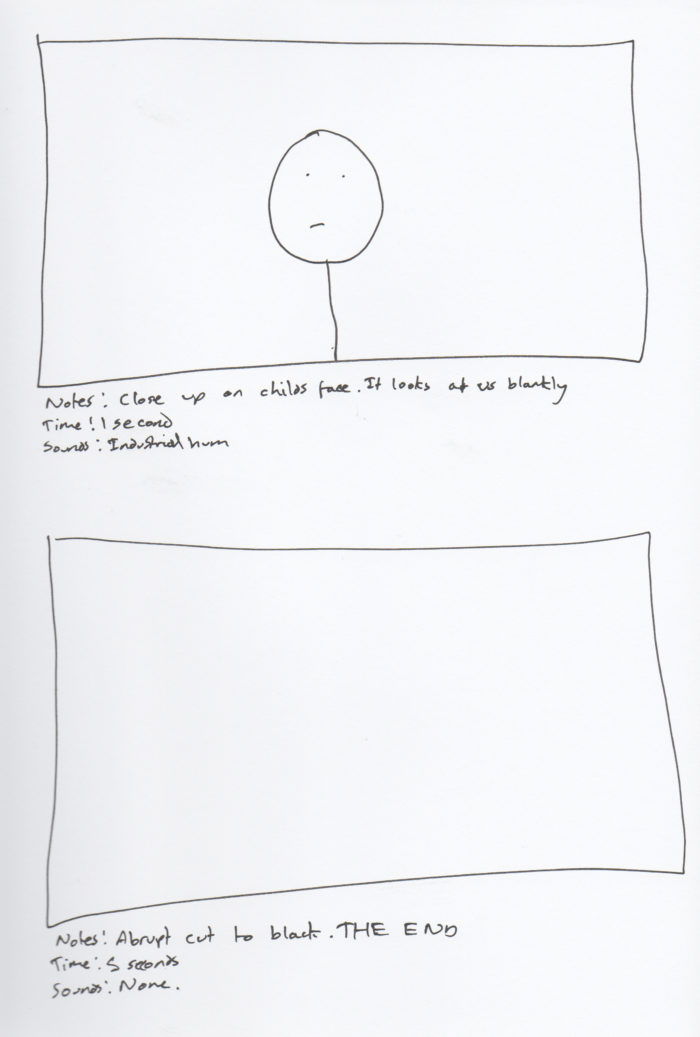

He closed his eyes and stepped across the threshold.

***

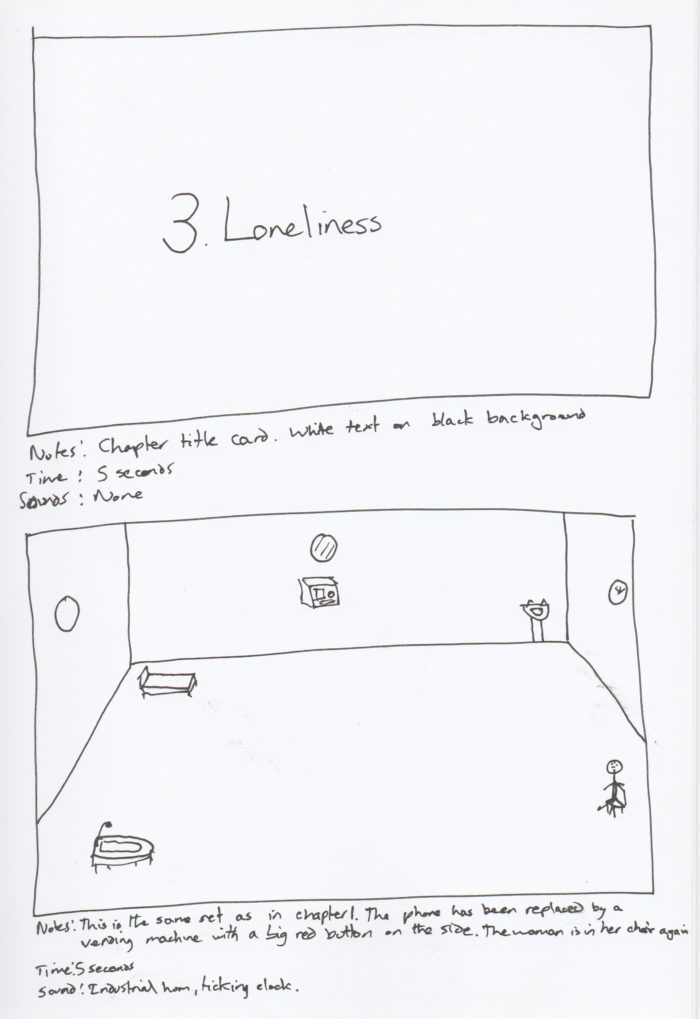

Chapter 3

__________

Notes:

1. The original version of the was written between November 2010 and November 2013

2. And this final edit was made in April 2016

3. This also has the same final sentence as The Three Doors And The Fourth

4. I’m not sure what this means

5. But anyway that’s why I have posted both of these today

__________

If you like the things you've read here please consider subscribing to my patreon or my ko-fi. Patreon subscribers get not just early access to content and also the occasional gift, but also my eternal gratitude. Which I'm not sure is very useful, but is certainly very real.(Ko-fi contributors probably only get the gratitude I'm afraid, but please get in touch if you want more). Thank you!