Most people seem to have a bunch of Halloween stories if you ask them, odd and unsettling events, all dressed up with dread and portent, urban legends repurposed as their own. A chance meeting with an old friend you find out later died years before, a kindly old lady with suspiciously hairy hands asking you for a lift home, a mysterious something brushing against your arm in the dark, that sort of thing.

Something teetering on the edge of plausibility. Something scary. Or scaryish, at least. Something spooky.

I’ve only got two Halloween stories, and I’m not sure either really fit that description.

The first one is pretty mundane. I made the mistake of going for a walk round here on halloween one time. I was on my own, just out for a stroll, and these arseholes ran past and egged me.

That’s it, that’s the whole story.

But I remember for a second thinking I’d been shot, not just the impact of it as that egg hit me in the stomach, but the sensation of putting my hand to my belly and feeling the wetness there, the sickly thickness of it against my skin. Then I held my hand up to the light and saw it was just a mess of egg, and that initial tremble of fear was overwhelmed by a somewhat tetchy annoyance.

Then came the mocking laughter from the kids as they sprinted away down the road, and my annoyance collapsed in on itself and I was left with nothing but a faint feeling of embarrassment that somehow lingered on for days.

My other halloween story is that last year I went trick or treating by car.

My brother turned up out of the blue in a brand new car. Some sports car. I don’t know what. I hadn’t seen him in months. He sat outside my house and beeped his horn and when I came out to see what was going on he wound down his window and the first thing he said was, “Let’s go trick or treating, Jill. Let’s go trick or treating in a car.”

He smiled. It’d been so long since I’d seen him. I loved that smile sometimes. I loved it now.

“I bet you’ve never been trick or treating in a car before,” he said.

And he was right I hadn’t.

The way he said it, too, as if this mundane idea was actually the absolute height of decadence, something so opulent there’s no conceivable way I could have ever done it before. Imagine it, his voice said through the wound down window, driving around town, demanding sweets from the innocent and the guilty alike. It’ll be glorious.

How could I say no?

In the boot he had two costumes. A wolf costume and a little red riding hood costume. We mixed and matched. I took the little red cloak and the wolf hands, he took the wolf’s head and the wicker basket.

“We’ll never pass as kids,” I said.

“Maybe I’m just a really tall kid,” my brother said, his voice slurred by the mask.

“Yeah right. A really tall kid driving a bloody car!”

“Well, okay, why not just say I’m your dad?” he suggested. “You’re short enough.”

He smiled. I hated that smile sometimes. I hated it then. Wide and knowing and filled with so many teeth.

“Urgh, okay then,” I relented. “I’ll need a mask too, though. Wait a minute.”

I went back inside, and came out wearing a kabuki mask I’d bought for some masquerade ball years and years ago. With the hood pulled up around it I looked suitably terrifying, although, I must say, the hairy hands were probably a bit much. But still, I liked them, and it was Halloween. It was going to be cold as hell tonight.

My brother looked amazing, standing there in his suit and tie, the wolf’s head on, leaning nonchalantly against this flash new car.

It was almost five, dusk already, just getting dark. We got in the car and sped off round the corner.

“Where are we going?” I said, cradling his wolf mask in my lap, running my fingers through its hair.

“I dunno,” he shrugged. “Just around. Wherever takes our fancy.”

He drove out of town first, round the bypass and then back again, getting a feel for his new car, accelerating up through the gears, before eventually we looped back towards the estate where we’d grown up.

He pulled up outside our old house, the one where we’d lived until I was five, till he was seven.

“How about here?” he said, taking his head from my lap and putting it on, placing one smile over another.

An old lady answered the door, almost old enough to be our grandmother, and my brother said, “Trick or treat?” as if he did this every year, as if he really was my father and I really was his little girl, too shy to speak.

While the old lady scuttled off to get us some sweets from the kitchen, I could see my brother leaning his head round the door, trying to get a look at our old hallway, our old stairs. Trying to see if there was anything the same, anything he remembered.

She came back with an apple for each of us, and some kindly words about being careful out there on a night like this. “And aren’t you a sweet little girl,” she said to me. I was too scared to reply and turned and ran back to the car. Behind me I could hear my brother apologising.

“I think she’s a bit scared, she’s only young… And, yes, yes, very tall for her age.”

The next few houses were just… houses. They didn’t seem to hold any special significance that I could see, weren’t the homes of old friends or relatives, as far as I could remember. But at each one they paid out handsomely in sweets, as if our journey was divinely ordained, good luck bestowed upon us by the god of cars, the angels of deceit.

After the fifth house, back in the car, my brother warming his ungloved hands above the heated air vents, he turned to me and said, “That was him. It was really him. Did you see that? It was him.”

“Who?” I said.

“Him,” my brother said, before revealing some half-remembered name from our distant past. “Oh god, I used to love him so much. I used to idolise him. He used to be so fucking cool. I can’t believe he still lives at home!”

He laughed loudly through the wolf’s mask for a moment and then, suddenly, shouted, “Oh god I hope his parent’s haven’t died. Maybe he’s inherited their house. Oh god, I don’t know. It could be anything, it could be anything.”

And then, a few minutes later, when we were halfway to the next house, “He used to be perfect!”

None of the next few houses provoked anything like this from my brother, although after one he said, “That was their mum, remember, the twins, I used to go round there all the time. Oh god, she looks exactly the same. Exactly the same. I used to think she was so old, I used to think everyone was so old. But they must have been younger than us, then, younger than we are now.”

It was about eleven when we got to the last house. I only knew it was the last house because my brother whispered, “this is the last one” as we crunched our way up the gravel drive and knocked on the door.

An old man answered. My brother held up our basket, a gingham cloth tucked neatly over the top, as if rather than being filled to the brim with deceitfully gotten sweets we had brought with us a nice picnic we wanted to share.

“Trick or treat,” we said together.

“It’s a bit late, isn’t it,” the old man barked at us. “It’s almost midnight.”

He slammed the door in our faces.

“Nice bloke,” I said.

“Well, he does have a point,” my brother said, looking at his watch.

We were almost back to the car when we heard the door behind us open.

“Here,” the old man said, tossing a chocolate bar in our direction. “Now go to fucking bed.”

And the door slammed again.

“Who was that?” I said. “It’s not the ghost of our father or something is it?”

“No, no,” my brother said, and then wouldn’t say any more.

We drove back to my house, put the fire on, and sat there while our bones tingled from the heat and our skin itched as life slowly returned to it. My brother tipped out the spoils we’d accumulated on the floor between us, a huge mound of sickliness, all the sorts of things I’d never usually eat. We took off our masks and gorged ourselves on it like ravenous animals hunched over a fresh kill.

The power went out at midnight. Even the fire cut out. My brother gave a ridiculously knowing theatrical scream at this sudden descent into darkness, and we both burst out laughing. After the laughter died down, we lapsed into a prolonged contemplative silence. I sat there in the dark, eating sweets from the pile on the floor around me, our phones out in front of us, their screens our candles.

Eventually we tired of keeping our phones awake, of the constant nudging and nurturing they needed to keep their flames from guttering, and we so let them splutter out, let the darkness take back the room.

I tried to scare myself with that old game we’d play as kids on nights like this – this isn’t a sweet it’s an eyeball, this one’s snot, this one’s not a liquorice lace it’s a wiggly worm! – but I think I’m too old to make myself giddy with squeamishness now. And in any case, it doesn’t really work when they’re your sweets, when you already know what they’re not, even if you’re not exactly sure what they are until you pop them in your mouth and bite them in half.

The church bells chimed one o’clock. I listened to my brother’s breathing in the dark, the ragged breaths that implied unseen tears. A chill went through me, and just as I was about to ask if he was okay he said, “I’m dying, Jill. I’m so sorry, I’m… It’s cancer, Jill. It’s cancer and I’m dying.”

I felt it like a knife to the heart. Like a bullet to the belly.

I didn’t know what to say. I didn’t know what to do. What can you say? What should you say? I still don’t know what to say and I still wish I’d said whatever it is I needed to say then but I didn’t. I couldn’t. I couldn’t and I didn’t and I should have. I should have known and I should have said and

and

and and and

In the dark, in the silence, that seething horrible silence, I reached out to hold my brother’s hand. And as my furry wolf-gloved palm clasped his own, he let out a piercing shriek of unabashed terror and scrambled away across the room in the dark, a stark fucking howl of anguish and horror and christ knows what that broke my heart forever.

“Oh, christ, Jack, it’s just me,” I said. “It’s just me. It was just these stupid fucking wolf hands, these stupid fucking gloves.”

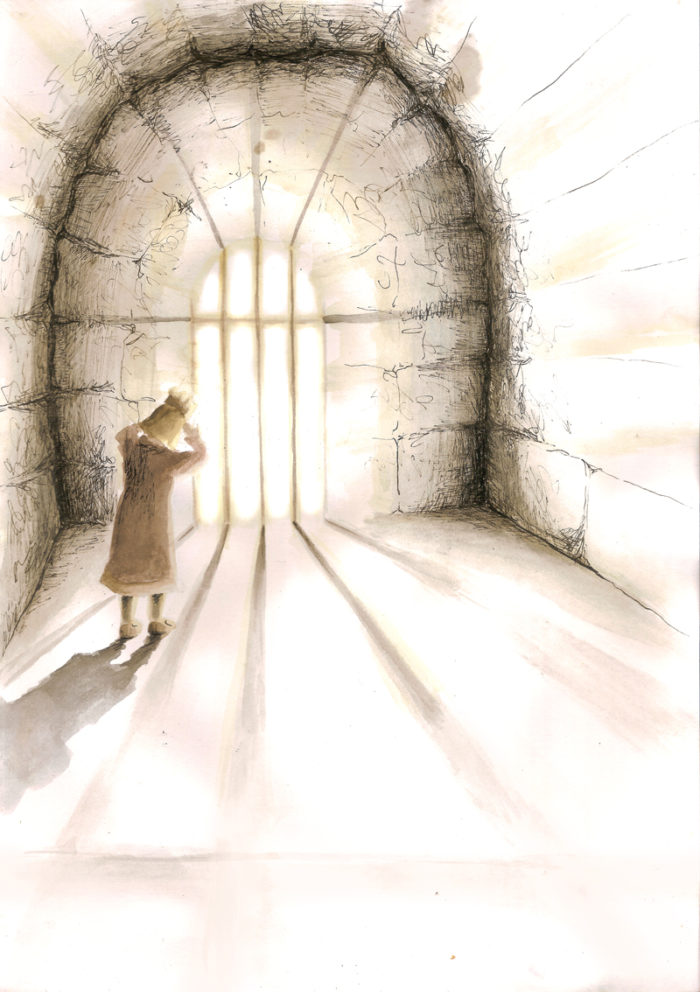

And for a moment then I wanted the silence back, wanted the silence of my failure and the dark of my heart to swallow me whole and never let me go, never have to let me show my face again, never have to let me live with the shame and the embarrassment and the grief, O god the grief.

But then the words came. I took the gloves off and held his hand in my own and the words poured out, poured out of both of us there in the dark, the words and the tears and every last remnant of our hearts.

__________

Notes:

1. Written on the 14th of September, 2018

__________

If you like the things you've read here please consider subscribing to my patreon or my ko-fi. Patreon subscribers get not just early access to content and also the occasional gift, but also my eternal gratitude. Which I'm not sure is very useful, but is certainly very real.(Ko-fi contributors probably only get the gratitude I'm afraid, but please get in touch if you want more). Thank you!