It had been quite some time since I had been fortunate enough to enjoy the pleasure of Sherlock Holmes’ company, my work and matters of the heart having kept me occupied well into the winter. So it was that I imagined I would be received with surprise upon my unannounced arrival at 221B Baker Street on that particular February night.

“Ah, Watson, you’re a little earlier than I expected,” he remarked to me as Mrs. Hudson left the room.

I was taken aback once again by the other-worldliness of the man’s deductions. “Holmes, how could you have known I was coming?” I spluttered.

“It is simple, of course. Have a seat, and allow me to explain.”

I sat down in the armchair opposite Holmes, and warmed myself by the fire while half-listening to his explanations. Eventually he finished, and, having given me ample time to both appreciate and applause his deductive brilliance, sat forward and passed a letter into my hand.

“It arrived this morning. Read it aloud,” Holmes directed, “Noting as you do any particular peculiarities that you find within.”

I removed the letter from its envelope and began to read, omitting the address and other extraneous details that I did not need to narrate. “‘Sherlock Holmes, I have read with interest the tales of your singular achievements and skills, although it is unfortunate that they appear with a less-frequent-than-I-desire regularity. It is my hope that you will be willing to grant assistance in solving a great mystery that has descended upon our house. My only child has vanished in impossible circumstances, and in this matter the police seem unwilling to assist. It is my contention, although not that of my husband, that this can only be due to our currently reduced standing within society, and the political pressures which emanate from these affairs.’ Below that is a name, ‘Emma Sowerby’, and a signature.”

“And your thoughts, Watson?”

“I would say the signature is a forgery.”

“Anything else?”

“The language seems to be intentionally strained, possibly suggesting the writer is not as educated as they wish to appear.”

“Good, Watson. Very good. Wrong, but very good none the less. Nothing more?”

“No, Holmes, nothing more,” said I. “Although I’m sure you have drawn some remarkable conclusions from the paper stock and what-not.”

“The first thing I noticed is the handwriting. As you can no doubt see from the backhanded slant of the strokes, this has been written by a left-handed writer. But, if you look closely at the smudging of the ink, it should be clear to see that this is someone unused to writing with their left hand.”

“I don’t see how that disproves my supposition of an uneducated impostor, Holmes. Perhaps they rarely have any need to write letters at all.”

“But if they were uneducated, the clumsiness of the language would be matched by an inexactness of spelling. No, this has been written by someone right-handed, and the only plausible reason for that is that they wish to disguise their true handwriting. Therefore, whoever wrote this letter is known to me, and wishes to conceal their identity from us.”

“Is it not possible,” I ventured, “that they have merely broken their usual writing hand?”

“I think not. Why, if they were injured, would they also include a signature? A signature is intended as proof of who you are, and an incorrect signature would lead one to assume that the letter is a forgery.”

I must admit that I became lost by the convolutions of his arguments from this point on, and rather than endeavour to recall facts of which I am uncertain, I will simply offer here a précis of his thesis. The letter had been written by a previous acquaintance of my esteemed friend, one that it could safely be assumed wished to have his revenge upon Holmes by ensnaring him, via this letter requesting his assistance, in an unsolvable case largely of his erstwhile adversary’s construction.

When I suggested that the entire story might be a fabrication, intended to bring Holmes to a place where he could be made to suffer harm, he dismissed my thoughts by pointing out that his diligence outstripped my paranoia. He had already spoken to the authorities, who confirmed that a child had gone missing from the house in question, that Emma Sowerby was indeed from a family of reknown, but who, through events that none were forthcoming to recount, lived now in an unbecoming state of penury. Furthermore, Emma Sowerby nor her husband, Henry, had ever had any dealings with Holmes, and indeed seemed ignorant of his existence when the Inspector had suggested to them that they might try to avail themselves of his services, a suggestion that as far as the Inspector knew they had never acted upon.

“So it is a trap?”

“Yes, but one into which we must descend. An innocent family have been attacked for no more reason than to pique my professional curiosity. Meet me here to-morrow morning at nine, Watson, and we can begin this adventure together.”

At eight o’clock precisely I reached Baker Street, hoping to arrive early and meet Holmes in his quarters. But Holmes was already in the street, standing exceptionally still in that way he would when most deeply in thought. When I greeted him he looked me once in the eyes and then turned and marched off on his way without even so much as a “Hello”. I followed as best I could, and by the time we reached our destination a mile or two hence I was quite out of breath, while of course Holmes looked completely untouched by his exertions. He knocked at the door, and, after perhaps a minute, knocked again with a forceful strike of his cane.

We were greeted by a maid, who had apparently been informed of our imminent arrival, for she did not wait for us to introduce ourselves but rather greeted us with a brusque, “My Lady has been awaiting you, sirs,” and conducted us through to the sitting-room.

Mrs. Sowerby was an impressive woman, her grief matched only by her evident capacity for self-restraint. Indeed, from her bearing, it would never have been apparent that her grief was complimented by a quiet yet implacable fury, yet we soon found out that this was so, for she was indignant at the lack of interest the authorities were granting her case.

“Mr. Holmes, I am glad you are here, and at the hour that you said. I have been left disappointed so many times at broken promises and repeated tardiness by members of our city’s constabulary. It is a pleasure to find there are still some who we can lay our trust in, even in these turbulent times,” said Mrs. Sowerby.

“This is my intimate friend, Dr. Watson,” said Holmes, introducing me. “Please speak freely before the two of us, Mrs. Sowerby, for the more you can tell us of the circumstances of the crime, the more it shall help us in forming an opinion upon the matter.”

“A little over three months ago, I gave birth. One of our rooms was turned into a nursery. Around this time, a number of pieces of jewellery and ornamentation, several quite expensive, and others of considerable personal attachment, went missing. By my deduction, the culprit was revealed to be the maid. She was let go forthwith.

“It was quite an unpleasant experience. At my husband’s urging the police were kept ignorant of the affair, and, as the maid continued to deny she was culpable even after our good grace in protecting her from the law, none of the pieces were recovered.

“Have you ever suffered such a violation, Mr. Holmes, to be robbed in this fashion, within one’s own home? It affects your every thought and action. Ever since, I made sure to lock the nursery, keeping the only key to it about my person, for of all of the possessions I treasured in this world, none were of any significance whatever compared to my only child. Such behaviour was irrational, or so my husband insisted, but subsequent events have proven my fears just, I am unpleased to say, rather than the delusional results of the paranoia of a panicked woman.

“A new maid was employed as quickly as could be arranged, and she has proven herself to be a great help and comfort to me. And yet, still my distress would not convince me to allow her into the nursery unaccompanied. It is hard to give out one’s trust again when it has been so greatly betrayed. So it was that I would accompany her into the nursery on any occasion that her duties required her to enter that room.”

“Tell me, madam, of the occurrences upon the day in question.”

“I cannot recall the morning of the day, for it was as dreary and conventional as the morning of any other day. I had put my child to bed in the nursery just before noon, for it is important for children to sleep after they have fed. I remember very clearly locking the door as I left, and continuing on to the sitting-room, where I was served lunch by the maid.

“It was at two o’clock when I returned to the nursery. I unlocked the door, and allowed the maid to accompany me in. While she managed the fire and lit the lamps, I went across to the cot and, in the very first instance, somehow noticed nothing amiss. But as I reached down towards my child, I then saw clearly that the cot was empty, and that my child had disappeared. It was at this point that I cried out, and my maid immediately came to my side. Soon the cook too joined us in the nursery, and although a search was made immediately no trace of my child did we find, nor any evidence of an intruder.”

“You say that you noticed nothing amiss at first. Were you distracted at any point, perhaps by the maid?”

“I was not,” Mrs. Sowerby said curtly. “Although the cot was empty, the blankets had not been disturbed, and were still spread out as if my baby slept beneath them. I believe it was nothing more than a trick of expectation which somehow prevented me from seeing the truth of what was there, or not there, upon my first glance. And it is important to remember, Mr. Holmes, that the lamps had not yet been lit, and the fire had waned while I had been enjoying my lunch, so that the room was quite dark, with strange shadows cast by the light from the hall. Indeed, I only mentioned it at all because you said to recount the circumstances of the day in the clearest of detail.”

“Indeed, I did, my dear. I am very much grateful for your frankness,” said Holmes. “And your husband, Mrs. Sowerby? Where was he?”

“My husband was at work. He is a clerk employed by a well-known shipping company at the West India Docks, assessing the incoming and outgoing goods and maintaining the accuracy of their ledgers. After the disappearance was discovered, a message was sent to my husband, and he returned home immediately, arriving perhaps an hour before the police, who had also by then been informed of the disturbance.

“I told them everything I have told you, Mr. Holmes, and although they assured me at the time that the culprit would soon be apprehended and my child returned to me, they seem no nearer to-day to discovering the whereabouts of my child, nor indeed have they uncovered any other relevant facts that might perhaps bring this case to its conclusion. When I complained about their inaction, they suggested that I perhaps should seek out the services of yourself, Mr. Holmes, for you have an uncanny talent, it seems, for solving even the most insoluble of cases.”

“It is a reputation I have done nothing to seek out,” Holmes said, flustered somewhat by the compliment. “And one that has accrued to me only by the diligence with which I carry out my duties in these matters. Let me assure you that I will not rest until this case is solved.

“There is something else you wish to tell me, my dear. Isn’t that right?” said Holmes, gently.

“Yes, you are correct. Although my name is Emma Sowerby, the family from which I am descended are the Asshetons of Abbess Roding.”

Holmes nodded his head in recognition, and turned to look at me with an expression of the utmost keenness. “The richest family in all of Essex, as I have heard it.”

“Indeed, Mr. Holmes. It is only due to an estrangement, brought on by the behaviour of members of my family, that I live as you see me now, in these most humble of surroundings. My father, a stubborn and often cruel man, would not countenance my betrothal to Henry, a man from a modest family whose only crime was in working for a company rather than, as my father expected, being the master of his own. On my refusal to accede to my father’s will in the matter, he cut all ties with me, and thereafter forced, by the malevolence of his being, the rest of my relations to do the same. I believe it is because of this that our case has not received the attention it has deserved.”

“Are you suggesting, my dear, that it is because of pressure exerted by your father that no solution to this mystery has so far been presented?” said Holmes.

“I am suggesting far more than that, Mr. Holmes,” said Mrs. Sowerby coolly. “I am my father’s only daughter. My mother has passed away, and my father is altogether too old and too stubborn by far to marry again. I am his only hope for an heir, and it is my belief that he has stolen my child to raise as his own.”

To this Holmes responded with a studied silence.

“You do not believe me, Mr. Holmes.”

“It is not a question of belief in you. If the facts of the case support it, then I shall believe in them.”

Mrs. Sowerby did not respond to this with anything other than an expression of sourness, and I thought for a moment she and Holmes might come to blows. But soon her countenance returned to its previous mask of self-restraint and she had us follow her to the nursery.

The chamber into which we were shown was on the same floor as the sitting-room. It was windowless and sparsely furnished, with a large cot by the fireplace, and a large painting adorning one of the walls.

“As you can see, the sole means of entry to the nursery is through this door. I alone have a key to this room, to which even my husband is not permitted to enter without my say-so. And yet, from here, in a busy household during the middle of the day, my child was taken.” Mrs. Sowerby stopped and looked Holmes directly in the eye. “My child, Mr Holmes.”

“Who else was here that afternoon, Mrs. Sowerby?”

“Only the cook and the maid. My husband was at work, and, I am afraid to say, our current circumstances allow only for a reduced staff during the week.”

“May I talk to them, madam.”

“Of course, Mr. Holmes.”

Holmes spoke with the cook first. She was a frightful lady, old and with a rather stooped back. She answered Holmes’ questions as best she could, and despite, as she kept insisting, having no head for facts or thinking, seemed to have a near perfect recall of every single morsel of food she had prepared that day. But beyond whetting our appetites with descriptions of her fare, she had seen nor heard anything unusual or interesting that day, nor in any of the others surrounding it.

The maid provided Holmes with a more diverting interview. Her skin was pale, her lips bloodless, and set against these the blue of her eyes blazed brightly. Her demeanour was one of great nervousness and she seemed unable to look at Holmes’ eager face for more than a few seconds without quickly glancing away, flustered, it seemed, by the intensity of his questioning.

Sherlock Holmes eased her down into a chair, and sitting beside her, patted her hand, and chatted with her in the easy, soothing tones which he knew so well how to employ.

“You must tell me your story,” said he. “A full account of the day in question, withholding nothing. Mrs. Sowerby has entrusted me in this case, and she has expressed her wish that you do the same.”

“I’ve worked in this household for the last two months, and in all that time never noticed nothing strange, nor witnessed any uncanny events, not of the type that occurred that day. Some houses you work in, sir, you get a feeling that they’re a bit, how shall we say it, strange. Not just the people in the house, either sir, but the house itself. I’ve seen some things that would make you shiver, you know. And some things worse than that, too.

“But this house wasn’t like that at all. If truth be told, it was a bit boring. Please don’t tell the Lady I said that!” said she. “But Mr. Sowerby was always away at his work until all the hours of the morning, and with Mrs. Sowerby afraid to leave the house, there wasn’t much to occupy the time. And there was no mysterious creakings about the house in the day, nor no strange commotions at night, nothing of that sort.

“Then on the day that baby went missing, everything changed. We left that nursery closed and there was a baby in there, and we came back an hour later, and it was empty. Not even the fire was burning. And the whole room as cold as a tomb. It was terrifying, sir, like the house had swallowed the child whole.”

“Now, now, my dear. There’s no need to look so frightened. There’s no such things as ghosts or ghouls in this world,” said Holmes. “For everything that occurs can be explained in such a way that, on knowing the secrets to the mystery, even a child will say, ‘Is that all? It seems so simple, now that I know the truth of it’.

“But beyond the disappearance, did you notice anything unusual at all that day, either before or after? Was there, for instance, an unexpected visitor at the door, or perhaps a commotion in another room that kept you occupied for longer than expected.”

“There was nothing of that sort of happening at all, sir. The house was very quiet, that day, the Lady not being able to afford much of a staff these days, as you can see, sir, and no visitors at all at the door. Not even the butcher with his meat, for he’d had said the day before that he was away to his mother’s that day, and so he brought round extra with him, so we couldn’t go short before he returned.

“And that child of hers was always as quiet as a mouse. No bother at all, that one.”

“And what of the nursery, my dear? Did you see Mrs. Sowerby lock the door to that room before she retired for lunch?”

“I did, sir. I was with her when she put the baby to bed, and then again when she unlocked that door in the afternoon. She likes me to do the fire for the baby. She says a young girl like me must surely be better at handling wood than an old ogre like the cook.”

The maid laughed lightly at this, and then went sombre again almost immediately when she caught Holmes intently studying her reaction.

“Can you be quite certain that no one else entered that room while Mrs. Sowerby was having her lunch?” said Holmes.

“Of course, I can, sir. I was in and out of the kitchen bringing her all her cakes and teas and what-have-yous she likes for her lunch, so I had to keep walking past the nursery door to get from the kitchen to the sitting-room. It was closed the whole time, and not a peep of noise from inside.”

Holmes’ interrogation of the maid was interrupted then by a commotion in the hall. We went out to see what was happening to find that Henry Sowerby had returned, and was clattering about noisily searching through the drawers of a sideboard in the sitting-room.

“Who the devil are you!” he exclaimed upon the sight of us, and he reacted with considerable ill ease when Holmes introduced himself to the startled man, ejaculating furiously towards Holmes with a tirade that it would be unbecoming to repeat here.

Throughout this outburst, Holmes maintained his usual quiet stance of curious forbearance.

“We are here at the insistence of your wife,” Holmes replied sternly. “Who is, I have found, a quite remarkable woman, if you may permit me to say so. If you believe I am here to find fault with you or your household, you are quite mistaken, unless that fault exists and merely awaits illumination by our pursuit of the facts.

“And if it is the potential cost of our services that causes this upset, as your outcry suggests, let me assure you that I do this not for monetary re-numeration, but because my intellectual curiosity has, as always, been piqued by such an apparently unsolvable crime as the abduction of a child from a locked nursery, and my heart stirred by the effect such a crime has had on such a person as your wife.”

“The child! The nursery! It’s all she ever talks about. It’s been two months, and never again shall there be anything else on her mind,” said Mr. Sowerby. “Well, if we must, I’ll show you what happened in the nursery.”

Mr. Sowerby strode away down the hall, and we followed him back to that barren chamber. Holmes and I stepped through into the room at his beckoning, but no sooner were we inside then Mr. Sowerby slammed the door behind us. There was a click from the lock, and when Holmes tried the handle it became apparent that the two of us had been locked inside.

“What a preposterous man,” I exclaimed. “Now I hope you have solved this case already, my dear friend, and the mysterious exit from this room is as apparent to you as a door would be to me. Because otherwise I fear we may be here some time.”

Before Holmes could answer me, we were interrupted by the sounds of shouting from the corridor. Mr. Sowerby, evidently still overcome by the ill-temper provoked in him by the presence of Holmes, and to a lesser extent myself, for he had seemed almost unaware of my presence, so focused was he upon Holmes.

“I told you,” we eventually heard Mr. Sowerby shout. “I told you not to contact this man. I told you to let it all alone. If this is to be our ruin, Emma, let it be known that it was you that brought it down upon us!”

After that final outburst the argument ceased for a while. From the hall we could hear the sound of stifled sobs, and when these stopped the ensuing silence was punctuated on occasion by what I at first took to be the slamming shut of doors, before eventually, after a bellowed shout of wordless fury from Mr. Sowerby, the whole episode was brought to a sudden end by the unmistakable sound of a gun being fired just outside the nursery door.

Holmes tried the door again, but it was solidly locked. After the gunshot, we had heard the sound of footsteps ascending the stairs, and since then nothing more. Our calls for help went unanswered, and we could only hope that the shot had been a warning aimed at scaring the women of the household out into the street, rather than, as we feared, a calamitous outbreak of murderous violence inflicted by the unhinged Mr. Sowerby upon his wife.

I tried to force the door open with some blows from my shoulder, but it was too solid to be affected in any way by my attempts. Meanwhile, Holmes was busily inspecting the painting on the wall, looking, I suspected, for an unlikely passageway that would hasten our escape.

“Watson, look!” Holmes said, pointing behind me to the smoke that had begun to billow in underneath the door. “Whoever locked us in here must mean us the gravest of harm.”

“We’ll be okay for a while yet,” I assured Holmes, pointing up to the high ceilings of the room. “But check the fireplace if you would, Holmes, to see if it’s blocked.”

“It’s no good, Watson. We’ll never fit up there.”

“I don’t expect us to, Holmes.”

“The baby, then? But surely it was too young for such an act?” Holmes said, his voice full of gentle confusion.

“No, Holmes, not the baby either,” I patiently explained. “If the chimney is unblocked, the smoke will begin to escape before it reaches the floor, and our chances of survival will be prolonged.”

“Ah, I see, I see. Very clever,” he said. “Very clever, indeed.”

Holmes scuttled over to the hearth, and, on his hands and knees, looked up the chimney.

“I have bad news for the both of us, my dear friend,” Holmes said. “It’s as black as the Thames tunnel up there, and as blocked.”

While we exchanged this back and forth, I had begun to lay the groundwork for our escape. I had carefully removed my jacket and started to work at the seam at the side, teasing forth a thread which I pulled at carefully until I had managed to extract a single strand of perhaps five foot long. I snapped it off and partially wrapped it around the index finger of my left hand as tightly as I could.

I pulled off my cravat and pushed it into the pocket of my trousers, and removed my waistcoat and shirt, placing them, along with my jacket, over the side of the cot.

“Whatever are you doing, Watson?”

Usually I would have been immensely pleased at having caused Holmes to express even a mild admission of perplexity at my activities, but I had entered that state of complete absorption in my tasks that I usually only came into at the operating table. I cleared a space in the centre of the room by pushing the rug towards the wall with my foot, and sat down cross-legged upon the stone flooring.

“Holmes, will you be so kind as to pass me the knife from the pocket of my jacket?”

Holmes did as I asked with a swift efficiency, leading me to imagine, as I often did, what a wonderful nurse he would make at my practice. I wiped the blade of the knife on my trouser leg, and then, with a grimace, plunged it into my belly, to the left of my navel. In one swift movement I pulled the blade across from to the right, creating a deep incision approximately 5 inches wide. From this wound, thick black blood spilled out and began to pool in the bowl my crossed legs had formed.

“Watson! Stop this at once, I beseech you,” Holmes pled.

But it was too late now to halt my plan, for my blood had been let loose and the pathways it led to were opened before me.

I examined my hand. My index finger was bloodless and white, all circulation having been restricted by the yarn I had tied around it. I cut the finger off in with single stroke, and the wound itself barely bled at all.

I untied the string from the stump of my hand, and knotted it tightly around the severed finger. I regretted not having brought any gloves with me, which in itself was an oversight considering how cold the chill February air was outside, for I would not now be able to easily hide the extent of my injury, and it would be a few days, if not a week, before the severed digit had grown back.

“Watson, have you gone mad?”

“No, no,” I murmured, a strange calmness having descended upon me. “Indeed, quite the opposite. Quite the opposite indeed.”

I looked down at the blood pooled between my legs. Although some of it had seeped out from the gaps between my legs, it had flowed quickly enough from my wound to overcome this, and had by now reached the tops of my thighs. This was quite deep enough for what I intended to do, so I removed the cravat from my pocket and stuffed it into the wound across my belly to help staunch the pulsing flow of my blood.

“Watson, I demand to know what it is you are doing!” Holmes quivered.

“I’m creating an opening.”

“Your blood will not lubricate the locks, Watson,” Holmes said, quite logically. “Nor provide any other notable means of egress from this chamber.”

“Not for us, Holmes, not yet,” I said. “Indeed, my friend, it is probably for the best if you conceal yourself in that fireplace for the next few moments, so as to shield your eyes from the unpleasant scenes that are about to occur.”

I did not turn around to see if he had complied with my request. Instead, I took up the thread holding my finger and held it in the air, giving it a quick tug to test the strength of the cord as it dangled down before me. As it did not immediately snap I hoped it would prove to be adequate for the job.

I wrapped the end of the thread thrice around the palm of my right-hand and lowered my finger into the pool of blood. It bobbed on the surface of the pool, floating on the thin surface that separated this world from the other. I pushed it under with the thumb of my mutilated hand and it sank down through the breach my blood had opened and descended into the world below until the string I held in my hand pulled taut.

“Can I come out yet?” said Holmes.

“No, Holmes, you must wa-”

The thread was pulled with astonishing force, pulling my hand down into the pool of blood with a heavy splash. My arm was submerged almost up to the elbow before I reacted, and the sudden surge forward of my upper body caused my legs to shift and a large quantity of blood spilled out from under my thighs and onto the floor.

Fortunately by the time I had regained my composure there was still enough blood pooled in the cradle of my legs for the enactment of my purposes, else I might have lost not just my finger but the majority of my forearm to the void. As it was, although the width of the opening was diminished, it was still wide enough to pull through what I had caught, and I began to haul my catch in.

I slowly withdrew my arm from the pool, which was thick with blood and other, darker, effluvium. My hand came free next, and then, inch by inch, I pulled the cord out of that dark pool, and at the end of the cord, snared with the bait of my finger, I had caught a creature unlike any on this earth.

An eyeless beast, it had a shell like blackened glass, and a segmented body, both bulbous and globular. Its fluted mouth quivered with effort as it tried to maintain its suction-like hold upon my finger.

I pulled the last of it out of its world and into ours, and I stood up then in triumph, the remnants of the birthing pool spilling against the flagstones beneath my feet.

“My god, Watson. Whatever can it be?” said Holmes, as he peered out from the fireplace and looked at the beast.

“Just a fish, Holmes, from the seas below.”

The creature floated there for a second, as, with its mouth still closed tightly around my severed finger, it bobbed up and down at the end of the piece of string like a balloon. Despite the way it lacked a face, it still managed to give the appearance of looking down at me with the haunted expression of a dying fawn.

This moment seemed, in the smoke-filled silence of the room, much longer that it could possibly ever have been, for, inevitably, the creature quickly exploded. Destroyed by the unnatural pressures of our world, its flesh was turned to a vaporous mist by the violence of its demise, and this mist mingled with the smoke that was by now causing both Holmes and I to cough and choke. I breathed this toxic mixture deep into my lungs.

My body was covered in a layer of its internal matter like a sheen of oil. Not having time however to clean myself, I simply put on my shirt and let it soak up the mess, finding it surprisingly difficult to button up my shirt due to the absence of my index finger. I left the cravat stuffed into the bloody mess of the wound across my stomach, not wanting to risk re-opening the cut before the next phase of action. The waistcoat and jacket I donned unbuttoned, and with my sleeve I wiped the worst of the muck from my face.

All the while I could feel the creature’s blood beginning to work its effect upon my mind. My blood was merely a conduit between our world and theirs, yet their blood was a conduit to all the planes of the great jewel of reality, of which our world inhabits but a single facet.

Acting quickly, aware that soon I would slip away into the passageways between the planes as my mind and body were transformed by the intoxicant I had inhaled, I hastily withdrew a box of matches from my pockets and set fire to the puddles of my own blood that had splashed like shadows across the floor. It is never wise to leave open a window, I reminded myself, no matter how small the gap. You never can tell what might find its way through. Or out.

I glanced over at Holmes. He was slumped against the wall, his gaunt face looking cadaverous in the kaleidoscoping light. I hoped the effects of the drug would not prove too disorienting upon him, for he was used to intoxications, even if they were much less potent than this unearthly concoction. The stillness of his body gave me hope that he would not fully comprehend the scope of the changes he was currently undergoing, for if he realised that his mind and body were untethering not just from space and time as he perceived them but from also each other it could become almost impossible to bring these two aspects of his self back safely together.

But similarly, if my attempts to effect an escape for the pair of us were to prove a failure and the smoke succeeded in choking the life from his body, at least it would be possible for his consciousness to survive. Dissipated and somewhat dulled it would be by its osmotic secretion across the crystalline rays of the multidimensional splendour of existence, but intact and still, unmistakably, Holmes.

Yet this image of Holmes’s mind, tiny, lost and alone in the great celestial void, gave me pause. Would that not be worse, perhaps, than a natural death? Would that not leave him at the mercy of forces even I would be hard pressed to fend off?

No, I could not allow myself to countenance failure. I needed indeed to be as quick as possible, so that his mind did not slip its bodily moorings and become lost upon the web of creation, for I could not take him with me where I went. It is impossible to chaperone one through the greater dimensions, for there constraint is precluded and all bonds can be slipped. As much as I would have liked to have been able to, out there I would not, in contrast to London, be able to show him safely the splendours of the realms, would not be able to take him by the hand and lead him safely through the thickets, would not be able to protect from harm like a father does his child.

I began to perceive shades of colour and forms of shape that were incongruent with the prosaic existence of everyday life. Soon I lost all sense of time and self and let the shimmering light take me.

It is perhaps one of the oddities of the mind that it cannot adequately recall the various states it is capable of existing within upon its return to another. In much the same way as pain can only be relived as a remembrance of the existence of that pain rather than felt as a recreation of it, and that dreams recalled upon waking lose the shape and colour of their visions as soon as they are exposed to the strictures of conscious thought, so it is that I cannot hope to instill in you, the reader, the full exhilarating feeling entering a state of existence untrammelled by either the linearity of time or the connectedness of space instills within you, not least because as I sit here and write, twelve long hours after the occasion, I can no longer adequately recall the wondrously animative sensation of it myself.

All I have is a partial recollection of the events that occurred. And, as with dreams, it is only upon waking that the contradictions become apparent.

As always I remember an instant of infinite understanding and the freedom of infinite movement within a space of infinite magnitude. And then, once this infinite moment is over, there comes a slow recovery of what we would understand as consciousness, which is in reality the loss of knowledge and perception of the uncorralled magnitude of the full planes of existence.

This point, where the two incompatible states of being overlap and merge, was what I required. For now I could conceive the three dimensional limits of our universe’s time and space, these necessary structural bonds that not only shape but birth our existence. Yet also I could still see many of the facets of the infinite crystal that exist beyond our own, and comprehend the vast cosmic complexities that underpin everything we take to be the completeness of existence. No longer were there three axes to space, but ten, a hundred, a million. I saw an infinite number of dimensions., and between each of those, an infinite number more.

Each point in space is a vertex, from which not one nor two nor three lines emerge, but all the lines. And each of these lines connect to every other point, near and far. And so each point in space is equidistant from each other point, and the truth of existence is that there is no space, there is no time, there just is. A single point, a single existence, a single universe, singularly, infinitely.

For this short while, I could move along these lines, and by taking a step in any direction, emerge in any location. I could move beyond walls. I could walk free from any prison. Sometimes I believe there is a reason humanity has settled in this world of three dimensional constraints. For every other world is a world without borders.

There is no mystery of the locked room there, nor the safety of one, neither. There are no ties that bind, no mazes from which it is impossible to escape.

Yet each passing second brought me closer to re-entrapment within three dimensional boundaries, the full multitude of traversable pathways slowly closing themselves to me as the changes wrought upon my flesh and thought began to wane. Soon locked doors would be as squarely shut to me again as they were a moment previously.

Holmes was still lay against the wall, his eyes staring blankly forward. I saw him from the front and from the back, from above and below and within. I could see his mind, all of it, a trillion sparks moving in a much larger sea of sparks, locked into patterns too complex to be mistaken for random occurrence. Already the edges of his perception were testing the boundaries of his body, motes of light floating away like tendrils down adjacent pathways before seeping back towards the whole, aware on some level that the two were no longer bound as one, but existed independently of each other. Yet these aspects of his consciousness were not yet brave enough to strike out on their own.

I wondered briefly what his analytical and thoroughly rational mind made of its current untethering. I hoped it would not do him any serious harm, and indeed, I would not have been surprised if such an experience as this would have provided him a great deal of benefit, if only it could have been delivered under gentler circumstance. But I had little time then to waste upon idle conjecture concerning the state of Holme’s remarkable mind, and so hastened myself to action.

I stepped out of the nursery and emerged in the kitchen. I found the smoke there so thick I could barely even seen the flames of the fire that raged throughout the room. The cook was sprawled out on the kitchen floor, having been killed by a single gunshot to the heart. It appeared that the fire had started behind her, a pan of fat having ignited on the stove at which she had been hard at work. Whether this fire was the work of happenstance or intent on the part of Henry Sowerby I could not tell.

With my next step I brought myself to the top of the stairs. I stood behind the door to Henry Sowerby’s study, my feet either side of the lifeless body of the unfortunate maid. She too had been killed by the bullet from a gun, an ugly wound having been torn in her throat by the blast, and her blood seeped into the thick amber-black carpet that lined the landing floor.

My next step took me from one side of Mr. Sowerby’s door to the other. The smoke from the blaze on the floor below had not yet penetrated into this dark chamber. Henry was sat in an armchair behind a large mahogany desk. His back was turned to me, and he stared into the shadows before him, the curtains on the windows having been drawn closed. The handful of his papers that were not burning merrily on the fire were strewn across the floor. He held a gun in one hand, while the other he jerked up and down in wild gesticulations, and, as I could see from multiple directions, he writhed his face into the most extraordinary contortions of pain and anguish.

I let aspects of my mind travel across the span of the room and occupy the same locality as his own. An osmotic process of accumulation began, and a jumble of images and emotions came to me then, not separately but simultaneously, as if I was recollecting a series of half-forgotten incidents from my own past, rather than having someone else’s past told to me. However, I shall endeavour to recount here the knowledge I was granted as linearly as I can.

Henry Sowerby had but one passion in his life and it was not love for his wife nor for his child. It was money, the one true greed of man, never satiated, never stalled. And so, having married Emma for her wealth and station, he was not prepared for her father disinheriting her, and having both unhappily married his wife and subsequently unhappily sired a child, he resented the shackles these events had placed around him.

The tragedy of the marriage was that Emma Sowerby truly loved her husband. Yet he was blind to this. His contempt for her was almost total, and he blamed all his difficulties on her. He believed himself a prisoner of his circumstances. He yearned for the freedom he saw presented to him every day at his place of work, for there he saw the riches that flowed in and out of the city, and every day he recorded in his ledgers a mere sliver of the unimaginable magnitude of the riches that awaited those who but had the necessary wealth to partake of it.

To buy a ship of his own was beyond his meagre earnings. The exponential growth of capital that shipping facilitated was closed to him, for there was no multiplier applicable to zero. It is impossible to start from nothing in this world.

He turned to theft. The few personal effects Emma had brought with her from the country to this depressing little house in the city may have seemed meagre to her, but to him every piece was worth more than his weekly wages, and each sum he sold them for on the black market brought him closer to his target. He stored his money in secret, and often spent idle evenings contemplating his hoard, holding in his hands the coins so he could feel the weight and reality of what he had accumulated.

Such misbehaviour could not go unnoticed for long, of course, and eventually his crimes were discovered. With a few nudges and misdirections, he managed to convince his wife that it was the maid that was the culprit.

His crimes at home ceased for a while, and he hoped that perhaps the birth of an heir might improve Emma’s father’s disposition towards her. But as the months passed, it became apparent that this hope would not be fulfilled. Again fate had betrayed him, for whatever whim of the body it was that decided her sex had chosen the fairer one, an act which ensured her grandfather held as little interest in naming her his heir as he did her mother.

Henry Sowerby therefore found himself forced to return to his previous habits. On the day in question, he sneaked into his home at a time when he knew his wife would be taking lunch, and it was with a duplicate key that he let himself into the nursery. His intent was set upon stealing the painting that hung above the fire, for he knew the price it would fetch on the blackmarket. A price so high he calculated it would be enough to grant him the necessary wealth to purchase his oft dreamed of ship, and so finally he would be his own master, beholden no longer to anyone except himself.

But as quiet as he thought his entry into the chamber had been, it was noisy enough to wake the sleeping child. He held his hand over the child’s mouth to stifle the cries, but when he removed it, the child beneath was dead.

Panicked, frightened, perhaps even grieving in his way, Henry Sowerby picked up his daughter’s body and fled the house, not forgetting, of course, to lock the nursery door on his way out, nor to leave as quietly as he entered.

He returned to the docks, not with a painting to be sold, but with a child to be interred. An accident, he screamed. It was an accident! He could not be held responsible for an accident. The child should not have cried out! His wife should not have locked that room! Her father should not have impoverished his own daughter!

But regardless of the causes, that afternoon, in a fruit-crate coffin filled with stones so that it would sink, his daughter was buried at sea. In the days that followed, Mrs. Sowerby wept on his shoulder, but he offered her no comfort, and told her no truths.

Fate once more had trapped him in its web. There was so much in the world there for the taking, if only you could gain access to the ladders that would enable you to reach. His wife had removed the first from his grasp with her failure to reconcile herself with her father, and not even the birth of their child proved enough to push it back towards him.

The second was blocked to him by his wife’s paranoia, the last remaining treasures of her house locked behind the nursery door, and watched over by his sleeping daughter like a slumbering dragon protecting its gold.

And it was her death that had kicked away all the ladders that remained, for since his every move was surely watched by the police. The ladders upon which he had hoped to escape were gone, and the walls of his dungeon loomed ever higher above his head. All that remained now was to wait for the dirt to begin being kicked in from above, burying him forever in this tomb.

No, no! Better to burn the dungeon to the ground and perish now, Henry thought, than to acquiesce to his sentence and die here unhappily half a life time hence.

All of this I learnt in the instant before he noticed me standing across the room from him. How much of it was true, and how much of it the justifications and distortions of ego and guilt? I cannot say for sure. What I can say, though, without a moment of hesitation upon my heart, is that Henry Sowerby was guilty of crimes for which only the hangman’s noose would suffice. Three women he killed to-day, and his daughter two months before them.

“How the devil-?” Henry Sowerby shouted, rising from his chair and turning to face me.

At this interjection, the outer aspects of my consciousness returned to me, and I was wholly myself once more. I saw Henry Sowerby clearly, unclouded by the taint of his perceptions.

“This is your doing!” Mr. Sowerby cried. “Couldn’t you have let us alone? Had we not suffered enough? What good would could come from the revelations your companion was set to unleash? All I wanted was a better life. Is that a crime? My wife… Oh god, look what you have done. Look at the blood you have unleashed. My wife, she was MY WIFE!”

With that final outburst, he pointed his gun at my chest and fired.

I moved out of phase with his world at the exact instant that the bullet passed through the space where I had been, and I watched from beyond Henry Sowerby’s conception of reality as the projectile continued on harmlessly into the wall Henry spluttered in confusion at my sudden disappearance, and while he attempted to gather his senses, I emerged in the unoccupied space behind him. Before he could turn around to face me, I grabbed him with both my hands and held him firmly in place.

“These bonds you strained against you tied yourself,” I told him. “The labyrinth you were lost in was of your own mind’s construction. The darkness that you blundered through could have been dispelled simply by the opening of your own eyes. Every action that you took was yours, and yours alone. The justice I serve here is limited in its scope and too late in its serving., but I do not hesitate to apply it. The only guilt I shall feel is the regret that I could not have executed it sooner.”

And with that I smashed his head down as heavily as I could onto the table, both of which cracked satisfyingly beneath the force of my swift and sudden blow, and his body slid lifelessly to the floor.

I looked up from the body of Mr. Sowerby and caught a glimpse of my reflection in the mirror upon the wall. My hands held high above my head and a look of crazed exultation held firm upon my face, and so it took me a moment to recognise myself in the apparition before me. It was the shock and shame of this recognition, however, which helped to bring me to my senses, and this wave of emotion flushed the last traces of the drug from my mind.

Returned now to a wholly solid and unremarkable state, I traversed the space of the room as any normal entity would, each step moving me across the floor in the usual fashion under which we conduct our perambulations. I quickly searched Mr. Sowerby, and found within the pocket of his waistcoat a key that matched the one Mrs. Sowerby had used to unlock the nursery.

I left his body lying where it had died, and quickly exited his study. On opening the door I was greeted by a thick cloud of smoke, and, holding my sleeve across my face, I stepped past the lifeless body of the maid, and quickly made my way down the stairs towards the nursery. Flames had spread from the kitchen and were steadily climbing the walls of the hall, and everything was dark and thick with smoke.

Emma Sowerby lay dead at the bottom of the stairs. A pool of blood spread out around her head, and as I looked at her I half expected to see her face begin to sink into it and fall through to deeper worlds, to see her body sliding across the floor and into the hole in one quick movement. Indeed of course it did not. Human blood is not enough to create a bridge between worlds. Yet it still took a concentrated force of will to make myself set my foot down in that dark patch and move towards the door.

I unlocked the nursery and went inside to rescue Holmes. He was lying where I had left him. His eyes stared through me, and for a few moments I feared that perhaps his mind had been irretrievably lost. But, as I applied rhythmic pressure to the palms of his hands, understanding began to return to his expression, and I hauled him to his feet and pulled him quickly through the smoke and flames into the street beyond.

Quite a crowd had gathered on the pavement, and it would not be long until the fire brigade and the police arrived at the scene. Knowing that the sight of Sherlock Holmes would quickly call attention to us from every direction, I shielded his face by wrapping my arm around his shoulders, using my jacket to help obscure his face. In this way I led him away, the shock of the morning’s events having rendered him quite, quite silent.

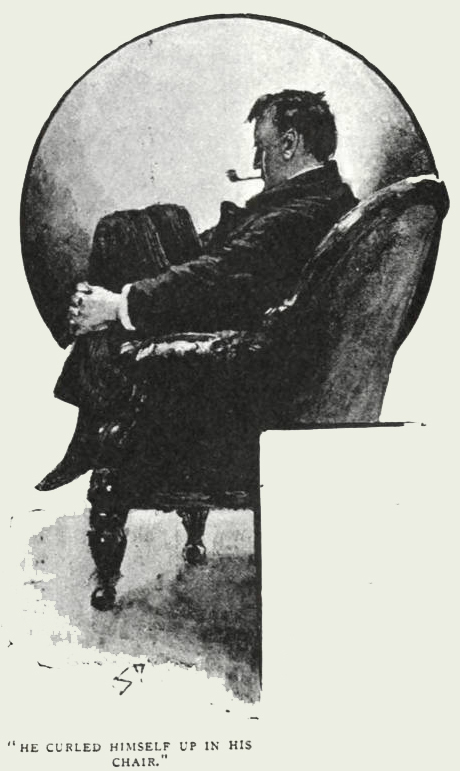

I returned Holmes to his apartment and sat him safely by the fire. He curled himself up in his chair, and I fetched him a drink of tonic water. As I handed him the glass he stared deeply at the contents, and then afterwards across to the gasogene with which I had prepared it. Shock had so slowed his usual catlike alertness that even I could follow the thought processes evident upon his face as he looked from the glass in my hand to the delicate orbs of the gasogene, which were safely encased in meshed wire to protect against the frequent explosions that afflicted the devices if poorly maintained. Even its bulbous shape was somewhat reminiscent of the form I had pulled out from the depths of my blood before him.

“Watson, wherever did you learn those things?” he said flatly. “Was it in Afghanistan?”

“Yes, Holmes,” said I. “Afghanistan.”

“From a fakir, no doubt.”

“Yes, Holmes.” It was an explanation onto which he gratefully hung, as he always did on occasions such as these.

I stayed with him in silence for a few hours more, until the duties of my marriage could not be foregone any longer and I got up to leave.

“Goodbye, Holmes,” I said, but received no reply.

As I reached the door his voice behind me said, “There never was a child, you know? Quite an elaborate ploy, and nearly flawlessly executed. But of course no fabrication can ever be perfect.”

“I really must go now, Holmes. I will call again within in the week, and perhaps you can outline the whole thing for me in your usual diligent detail. Good-evening.”

“Wait, my dear friend. Do you not want to know the solution to this great puzzle? Surely you’re mind cannot be at ease until the solution has been presented to it.

“You saw the scars upon Mrs. Sowerby’s face, I trust, Watson?” Holmes looked keenly towards me. “Not acne, as you might have assumed, but marks left over from a recent case of German measles. No doubt contracted during pregnancy. An unfortunate side-effect of such a disease is the often fatal consequences it has upon the foetus. It is the case, I am certain, that her child died, if not in the womb, then at birth, and that the nursery has been empty ever since.”

I paused at the door, and listened to his explanations.

“Yes, yes,” he said, excitedly, as his imagination began to take hold. “As the child was of course the means by which she could convince her father to accept her back into his graces, she hid the death of her child from her husband, her estranged family, and even her staff. Of course, the fabricated accusation of petty theft levelled at her previous maid allowed her an excuse to keep the nursery locked..

“To maintain such a charade for a number of months is, I must say, a very impressive achievement. And for it all to be undone by a mere stroke of bad fortune, almost unbelievable in itself.

“I’m sure even you noticed, Watson, the pins with which the maid fastened her hair, and the smudges of grease upon her fingers. To hire a maid who was not only an actual thief but also an expert in picking locks, after the spurious firing of a maid for those very claims. What bad luck! What exquisite, unbelievable irony!

“Of course, on the day of the claimed disappearance, Mrs. Sowerby must have seen this maid sneak her way into the locked room. On the realisation that her ruse was on the verge of being discovered, she herself went into the nursery and there made her ‘discovery’ of the missing child. Knowing that her maid would not contradict any of her testimony, she was free to spin the yarn she told the police.

“Once it became clear we were on the cusp of solving the case and exposing her ruse, she locked us in the nursery and set the house on fire to cover her tracks.

“It was fortunate, was it not, Watson, that your prompting me to check the chimney allowed us to discover it concealed an exit to and from that nursery of hers.

“Without that stroke of luck we would surely have perished. Instead, we discovered not one but two solutions to the locked room mystery.” Holmes looked at me then with a wistful look in his eye. “I wonder if we shall ever catch her. Quite a brilliant adversary. Quite, quite brilliant.”

He stumbled absent-mindedly to the drawer in which he kept his various medicinal remedies, talking loudly with excitement as his imagination raced out ahead of him.

“The letter! Do you remember the letter, Watson? It was just as I said. The maid, to soothe her conscience, brought us into it, for she knew that we would solve the case, and discover the sad truth of the tale.”

Already the day’s events had been re-drawn into more intricate, if conventional, forms. I am certain that by the time I see him next, any lingering inconsistencies will have been removed, and the whole tale shall mesh together perfectly like the cogs in a clock.

I felt saddened, I must admit, by Emma Sowerby being recast as the architect of the crime, rather than the victim, but accepted that his version of the tale would cast a greater spell over our readership than the sad truth of the matter ever would. His skill in the construction of a compelling narrative was, without doubt, the finest I had witnessed in any of my patients, and the way in which he drew parallels between two disparate details to make their connection seem undeniable to the reader was a source of constant amazement to me.

“The passageway puzzles me, Watson. Presumably the maid, having targeted the Sowerby’s, knew of its existence, but if she did, why the need to pick the lock?” Holmes murmured to himself, drowsily. “The painting! Of course, it was the painting all along. I knew when I inspected it that it was a masterpiece. A prize worth returning to steal, of course, but a prize too big to sneak out via the passageway. Yes, yes, fascinating, wouldn’t you say, my dear Watson?”

“Yes, Holmes, it is indeed. A fascinating day all told, I would say.”

After that I said my good-byes once more, and left him to indulge himself more deeply in the various solutions that he found so comforting. From the street I glanced back up at the windows of his rooms. Holmes had risen from his chair and put down his pipe, and he stood with his back to the window, swaying in a way I found disquieting. It was only after a moment that I realised he held his violin in his hands and his unnatural movements were simply the measure of the energy of his play. I wished I could return and listen to the sounds he currently conjured, to witness the euphoria as his mind came to terms with the events of the day. Instead, I turned and walked away, and by the time I reached my house I had begun, quite happily, to whistle.

__________

Notes:

1. Written between July 2014 and July 2018

2. Although actually mostly in July 2014 and July 2018

3. With very little occurring in between

4. Some of the sentences have been lifted directly from the original stories.

5. By Arthur Conan Doyle

6. But most of them have not

7. While the illustrations are by Sidney Paget

8. And are taken from here