It was perhaps an hour after midnight on the night before Christmas when the discussion amongst those of us still present turned to the true nature of hell, and more interestingly, whether one would recognise it if indeed we were to find ourselves there (an outcome that most of us acknowledged, due to the realities of the worlds of business and politics we inhabited, was for each of us a distinct possibility, though not yet, we hoped, an inevitability).

There were only seven of us left by then. Earlier in the evening it had been announced that a storm was approaching, a surprise given the meteorological forecast, and most of the members of our small but exclusive society left upon this pronouncement so as to miss the worst of it. For those like me, however, where the journey home was not a practical one to make at so late an hour, the decision to see out the storm in the comfort of our favourite armchairs was quickly made, and we settled in for the night.

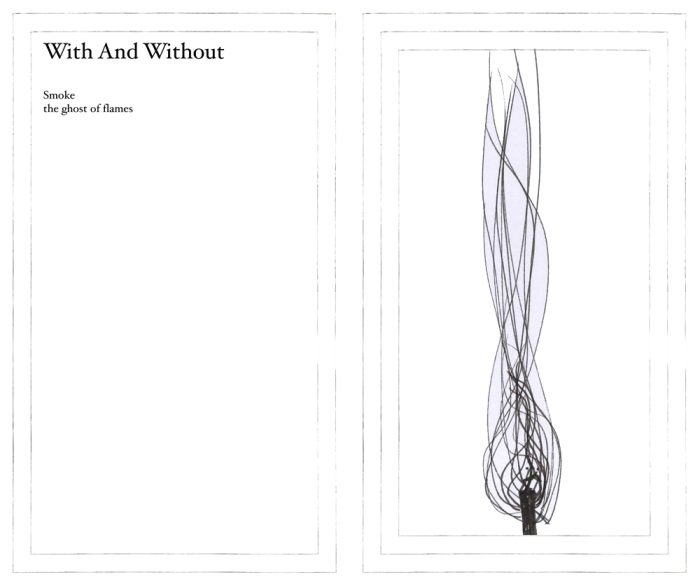

The fire had originally been lit more for its atmospherics than its heat, and now the flames and the smoke provided us with a suitable ambience for our heretical discussions, amplified these last few hours by the periodic flashes of lightning that pierced through the curtains as surely as they would have through our eyelids, should any of our number have wished to rest their eyes and doze through the evening’s confinement.

And if the lightning was not enough to keep us from our slumbers, then the roar of thunder that accompanied each flash, and the ceaseless beating of the rains, which hammered like the fists and the feet of the mob against the window panes and the roofing tiles of the annex in which we were seated, undoubtedly were.

The seven of us there that night were: The venerable Mr Eden, longstanding patron of our club and the man, it must be acknowledged, in whose shadow all of us still stand; Mr Canning and Mr Lawrence, retired now but both still much admired for how they dealt with the mutineers in their day; Mr Bourke, a visiting professor emeritus from Dublin whom I had never previously met; Mr Baring, my great friend and long-time companion, and on whose account I had journeyed to the city earlier that day; myself, being as I am a gentleman, as you know, of no particular renown; and Mr Curzon, a taciturn fellow only recently inducted into our circle, who had, I believe, made his fortune in shipping, and at the very least had a reputation for being well-travelled and knowledgeable even by the standards of the rest of us fellows.

The evening’s conversation initially concerned little more than the traditional greetings and homilies of the season, such as each of us have said and heard on untold occasions before. There is a circularity to Christmas which makes the present feel somewhat indistinguishable from the past, and it’s insistence on both public and private cheer brings its own difficulties, shall we say, even at the best of times. And so there was an undercurrent of irritation in much of what was said, as there always is in the slightly hollow exhortations to peace and goodwill that are customary at this time of year, though of course gentlemen such as ourselves try our damnedest to hide it.

Soon the subject of our politely expressed displeasure turned to the vagaries of the weather, and the various complications and alterations to our plans this unexpected storm would likely cause us, and then, too, of course, the insipid company and ungrateful nature of many of our distant family members upon which we were expected to play host in the days to come.

But luckily the season lends itself well to tales of a more unpleasant nature as well, and quickly we gave up any pretence of civility and good manners, Mr Baring relating to us with evident relish the latest news concerning a series of unsolved murders in one of the neighbouring counties, the particulars of which had been kept quiet by the local press at the behest of the region’s police force.

Yet Mr Baring, through his contacts within the constabulary (which proved so beneficial to his commercial interests), had been informed of some of the more garish details of the crimes, and was taking great pleasure in describing to us the monstrous and macabre violations to which the victims had been subjected.

“The perpetrators of such crimes may evade the law of our lands,” said Mr Eden into the silence that followed Mr Baring’s evocations. “But upon their own death, justice shall prevail. There are some judgements from which none are spared.”

It was this comment that turned the conversation towards the theological. Mr Eden, a man of the law in his youth, inevitably saw hell in the simplistic terms of his profession, envisioning it as some great and flawless penal colony, where every judgement would be ineluctably correct, each sentence eternal, and the punishments robust and inescapable.

Mr Canning and Mr Lawrence here agreed with Eden, the pair still playing, after so many years, the dutiful proteges. But disagreement soon came in the form of Mr Bourke’s contention that if hell was little more than a divinely administered prison, its very scope for inflicting pain and torment upon the soul would be limited. Indeed, it was his opinion that any system of hell that revealed itself openly to those it had captured would be resisted, and therefore rendered, eventually, ineffective.

“One would settle in for eternity,” he said, his voice carrying with it the authority of a lifetime of lectures upon, I suspected, this very subject. “For as we know, in war the daily horrors inflicted upon the flesh are steadily countered by a growing numbness to pain, and in famine increasing psychic detachment from reality inhibits the terrors of the mind from flowering into full bloom.”

Further, he explained, hell would need to operate without the fear of death (for how can there be death in an infinite system), while also foregoing the fear borne of concern for those we loved, for in the eyes of God each of us are judged for our own crimes only, and not for those of others, and so, no matter what our infernal captors could threaten us with, we would know the still-living were beyond the scope of their powers. Within these limitations the ability to truly strike effectively at the heart of man would be nullified and rendered void, he contended.

“But what of corporal punishments?” asked Canning. “As all of us here know, pain is a useful tool when wielded by the hands of the righteous and the just.”

“Pain itself is not enough,” he said. “We can endure mere pain for longer than we should.”

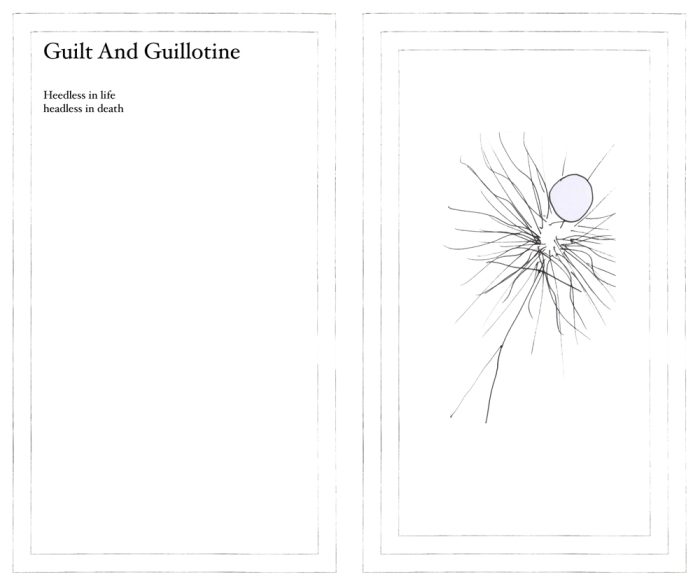

And at this he held up his own hand, and with a quick twist with his other, removed it, holding up for all to see his mutilated wrist, and the scars that ran like lava flows down towards his elbow.

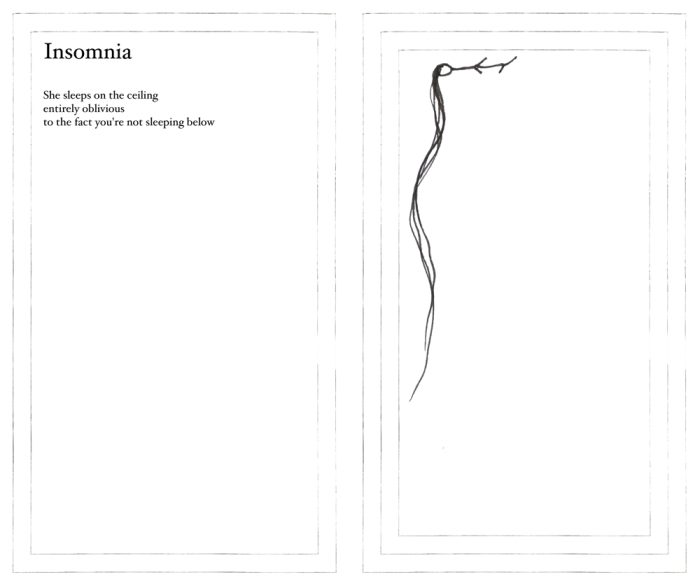

“No, there are two possible forms that hell could conceivably take,” Mr Bourke claimed, after a suitable pause for us to appreciate his theatrics. “One would be a series of nested dreams, in which, on waking from a nightmare, we would find ourselves trapped within a nightmare greater still. And from that eventually we would wake, and so on, for eternity, with each layer beneath more frightening than the last.”

“For in that sleep of death what dreams may come,” I murmured, recalling some quotation or other that had been taught to me in my youth.

“Very good,” the good professor said to me, with a nod of approval, before returning to his conjectures. “And the other possibility, the one that seems more likely – and, indeed, the more often I dwell upon the problem, the one that seems to me the only true possibility – is… this!””

He held his arms out wide, his truncated left arm granting an asymmetry to the gesture which rendered it somewhat disconcerting.

“The club?” asked Mr Baring, already perplexed by Bourke’s arguments and now almost completely lost as to his point.

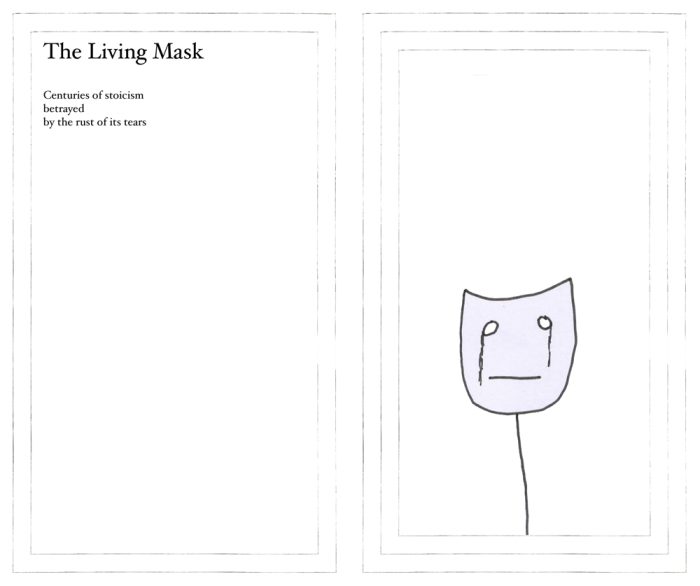

“I speak of the world itself,” Professor Bourke said. “For a true hell would maintain the appearance of reality. It is only in the here and now, in the everyday mundanity of existence, that the corruption of the soul can retain any meaning.

“To be corrupted in hell carries with it no lasting shame. Of course we would be corrupted in hell. Of course we would be humiliated and perverted and defiled until we were a broken shell. How could we expect anything else?

“To be corrupted in life, however, to have to live with that corruption, to see the effects of our actions, and to be forced to live with what we have done, to have that gnawing fear, that dread, within your heart, knowing that at any time you may be confronted by your past misdeeds, or be forced into committing misdeeds anew. Is that not a punishment worthy of hell itself?

“To be forced, not by circumstance but by the very failings of your own soul, to behave in terrible, horrifying ways, out of nothing more than cowardice, or desire, greed, laziness…

“To live to see all the things you believed in and fought for, the better world you hoped to bring about, all those slow steps of progress undermined, hollowed out and eventually swept away by a tide that brings back to us nothing but ever increasing hate and horror. And all of it of our own doing, all our justifications for those same deeds revealed to be no more than the self-serving lies of the common criminal we here so like to judge and have without mercy condemned more times than we can ever hope to remember.

“Now that,” he said, as he began to screw his hand back into place. “That is a hell to be feared. A hell that would be worthy of its reputation.”

I again responded to this with a quote – “I began to learn to hope and what brings a more bitter despair to the heart than hope destroyed” – before Eden, in his diplomatic way (perhaps to calm the coming bluster of Canning and Lawrence), said, “Perhaps it is both. Or neither. Perhaps the passage of time itself is punishment enough. The realities of our lives and misdeeds reduced to mere footnotes in one of Professor Bourke’s many unread histories.”

“The horror,” Canning and Lawrence said, with forced jollity, and Bourke too repeated the phrase quietly as he slumped back into his chair, and then the room fell into a deep and not especially comforting silence, in which we listened to the beating of the rain and indeed to the beating of our own hearts for what seemed like an age.

Just when it seemed like the silence would continue for the rest of the night, as we all began to drift off into ruminatory slumbers, it was broken, unexpectedly, by the largely forgotten figure of Mr Curzon, who let out a dry and desperate laugh that caused us all to turn in near unison towards his chair.

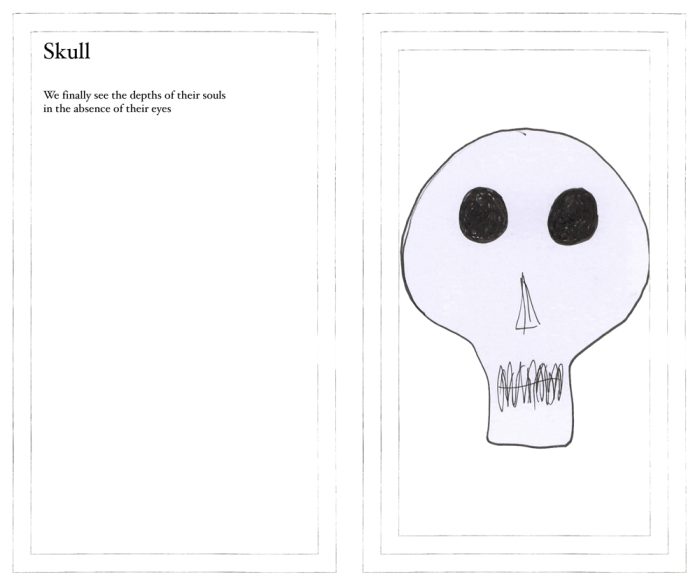

He leaned forward, his face rising from the shadows and into the illumination provided by the fire, and as he turned to face us, the shadows thrown upon his skull by the flames seemed to shift and shiver around the fearful rictus of his smile, and in his careful, calm way, he began to recount to us the following tale.

“It was perhaps an hour after midnight on the night before Christmas,” he said. “When the discussion amongst those of us still present turned to the true nature of hell, and more interestingly, whether one would recognise it if indeed we were to find ourselves there…”

__________

Notes:

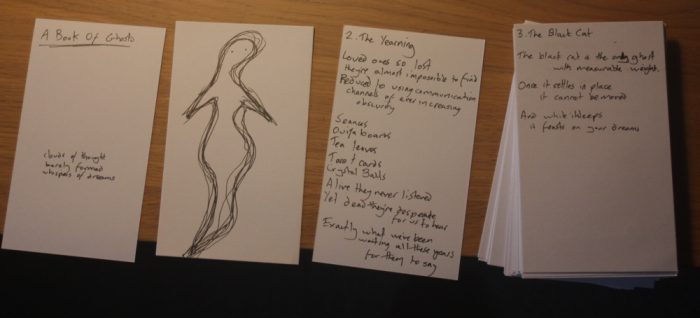

1. This is a reworked version of On The Nature Of Hell

2. I was asked to turn it into a Christmas ghost story

3. So I did

4. In November 2024

5. But then it wasn’t needed anyway

__________

If you like the things you've read here please consider subscribing to my patreon or my ko-fi. Patreon subscribers get not just early access to content and also the occasional gift, but also my eternal gratitude. Which I'm not sure is very useful, but is certainly very real.(Ko-fi contributors probably only get the gratitude I'm afraid, but please get in touch if you want more). Thank you!